Manuscript vs Printed Books

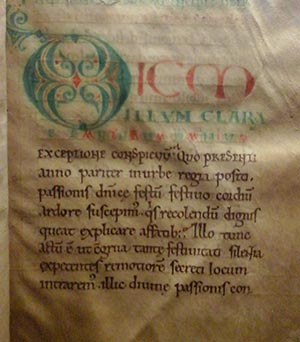

Figure 1: University College MS 104 fol. 2r. Julian of Toledo, Prognosticon futuri sæculi (11th century) – click for larger image

On 21 May 2022, guests at the William of Durham day were shown a slide-show and exhibition of manuscripts and 15th century printed books from the Library’s collections. It was fitting that we spoke about these collections, most of which were gifted to Univ, to a group of people who are continuing Univ’s long tradition of benefaction by making provision for the College in their will.

From medieval scribes copying manuscripts by candlelight to the 15th-century innovation of the printing press and movable type, books have been central to Univ from as early as 1292. The College statutes of this year include provision for a collection of books to be kept for use of the Fellows. Our oldest manuscript predates Univ’s foundation by around 200 years [fig.1: MS 104]. At the William of Durham event, we wanted to use some of Univ’s collections to show the transition from manuscript to printed books.

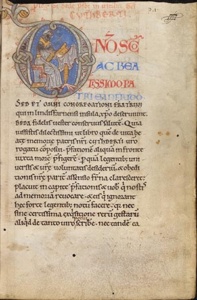

Figure 2: University College MS 165 fol. 2r. Bede the Venerable, Vita et miracula S. Cuthberti (12th century) – click for larger image

The word “manuscript” comes from the Latin, “manu scriptus”, which means hand-written. Scribes in the medieval period were mostly monks, who wrote on prepared animal skin (vellum or parchment), sometimes adding in decorative intials or other embellishments. Because they took so long to produce and used costly materials, manuscripts were valued possessions in the medieval period.

In the middle of the 15th century Johannes Gutenberg, probably inspired by a much older Chinese technology, altered a wooden hand press used for wine-making, so that it could print from movable type. He also perfected a method of casting pieces of metal type which meant that they could be used many times over, vastly speeding up the production of books. The earliest books printed with Gutenberg’s technology are called incunables – from the Latin “incunabula” which means “swaddling clothes”. The term has been used since the 18th century to indicate books printed before the end of the year 1500.

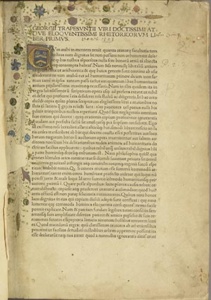

Figure 3: University College W.30.15 fol. 1r. George of Trebizond, Rhetorica (Venice: Vindelinus de Spira, 1471/2) – click for larger image

Viewing one of Univ’s most important manuscripts, Bede’s “Life of St Cuthbert” [fig. 2] alongside our oldest printed book [fig. 3] illustrates the way that books produced using the new technology of printing mimicked the form of the medieval manuscripts. Early typefaces were designed to look like scribal hands and printers left space for initials to be added by artists after printing. Owners were able to signify their wealth by commissioning elaborate initials and marginal illustrations to their books or by paying for highly decorative leather bindings.

Curiously, in our oldest incunable, there is a note on the first page of the printed text suggesting that it was printed in Venice in 1523. The city is correct, but the book was in fact printed in 1471 or 1472. The text, George of Trebizond’s Rhetorica, is a relatively common incunable, with forty-two copies known to survive.

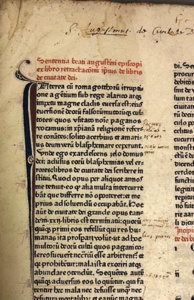

Although Univ’s Library does not have any examples of Gutenberg’s work, we have one incunable [fig. 4] that was printed by one of his apprentices, Peter Schöffer, in 1473. Schöffer is best-known today for printing, in collaboration with Johann Fust, the “Mainz Psalter” which is the second major work, after Gutenberg’s Bible, printed with movable type in the West.

Figure 4: Univ. Coll. b.3: Augustine of Hippo, De civitate dei (Mainz: Peter Schöffer, 1473) – click for larger image

Our text was one of Schöffer’s later publications and a 15th century best-seller, with at least 18 editions printed in the 15th century. The text is an edition of Augustine of Hippo’s book De civitate dei (in English, “The city of God”), one of his most popular works. Augustine wrote the book to reassure Christians after the sacking of Rome by the Visigoths in 410 AD, when some claimed that Rome’s decline was caused by the citizens’ move from the traditional Roman religion towards Christianity. That the text was still being printed 900 years after Augustine’s death is testament to its enduring importance.

The Library’s collections of manuscripts and incunables give us a valuable window into Univ’s past. Watch this space for more Treasures showcasing our manuscripts and incunables.

In addition to the recommendations below in our “Also Enjoy” section, you may also like to explore our previous Treasures Scribbling in Books and Chronycles of the Londe of Englond.

Published: 30 May 2022

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.