Tales from the Archives: Shelley and Univ

To mark the bicentenary next month of the death of the great poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822), we will devote our next two Treasures to Shelley and his turbulent relationship with Univ. For this first Treasure we will look at some of the archival records held in the College which relate to his Oxford career.

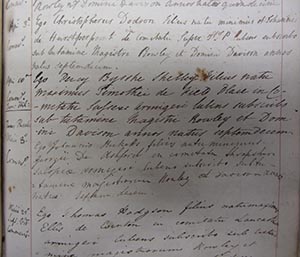

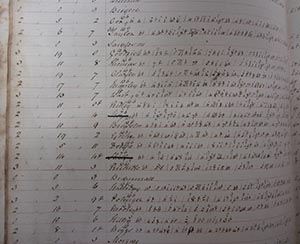

We start, as one should, with Shelley’s entry in the Admissions Register. His flamboyant handwriting does stand out on the page (image: Ref. UC:J1/A/2).

Our Admissions Registers began in 1674. They are, so far can be judged, unique in Oxford for their thoroughness, for we have a good example of the handwriting of every member of Univ, as well as useful information on their family and age, for almost 350 years. So in Shelley’s case we learn that he was the oldest son of Timothy Shelley of Field Place, Sussex, esq., and that he was 17 years old.

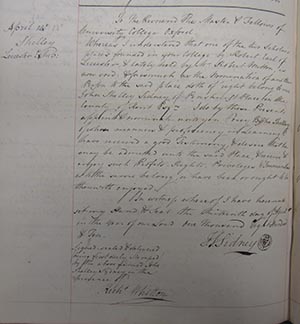

The Admissions Register does not tell the whole story of why Shelley came to Univ. In particular, his father, Timothy, had himself come up to Univ in 1774. There was also a special family link, as revealed in this entry in the College Register, dating from 13 April 1810, in which Shelley is given a Scholarship at Univ (image: Ref. UC:GB3/A1/2 fol. 145r).

Two Leicester Scholarships had been endowed by Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester on his death in 1588, and he had specified that they should always be nominated by his senior descendant. In 1810 the descendant doing the nominating was one John Shelley Sidney. The name is significant. In fact, Sir John Shelley Sidney was actually born John Shelley, but took on the surname of Sidney on succeeding to some estates inherited via his mother. John Shelley Sidney was Timothy Shelley’s younger brother, and John was therefore Percy Shelley’s uncle. It is an amusing paradox that Shelley, the passionate radical, was admitted to Univ thanks to his useful family links.

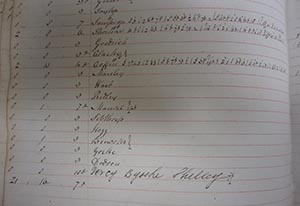

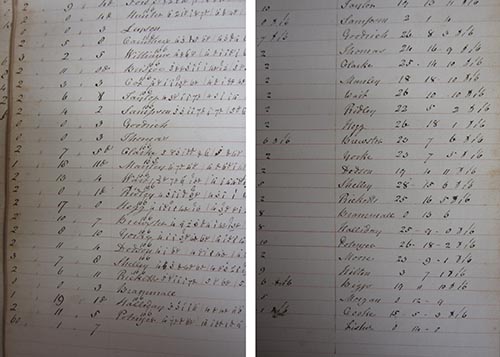

Interesting evidence about Shelley’s time at Univ can be found from the College’s Buttery Books, which recorded members’ expenditure in the Buttery. New arrivals would sign their names in the Buttery Book at the same time as they signed the Register, and Shelley’s entry can be seen in image Ref. UC:BU4/F/80.

Buttery Books are very valuable sources for tracking when a member of a College was actually resident there. Some years ago, a Treasure devoted to Buttery Books from the early 1640s showed how they could be used to reveal the College emptying as the country slid into civil war; see Witness to civil war.

In the case of Shelley, the first thing to note is that he does not start paying for any food or drink until the week of 19 October 1810. This time lag between an undergraduate matriculating and his entering into residence was not unusual in the early nineteenth century: we know from other sources that it was common for a young man to be brought up to Oxford by his family to be admitted to a College, and then return home until accommodation could be found for him. This evidently happened in Shelley’s case.

Each opening in a Buttery Book records a week’s expenditure, and at the end of each term these totals were all added up. They reveal something very unexpected about Shelley, which is that he was one of the most extravagant members of the College. His batells bills are regularly the highest among his contemporaries, as can be seen from the week of 23 November 1810, where he is charged £3 7s 8d, significantly more than anyone else listed (below, left Ref.: UC/BU4/F/80) and, (below right Ref. UC:BU4/F/80), at the end of Hilary Term 1811, we can see the size of the bill which he has run up (almost £30), especially in comparison with his contemporaries.

Ref.: UC/BU4/F/80 – left week of 23 November, second opening & right end of Hilary Term – click for larger image

During his time at Univ, Shelley quickly became friends with another undergraduate here, Thomas Jefferson Hogg, who had come up in February 1810, and who shared many of Shelley’s unorthodox beliefs.

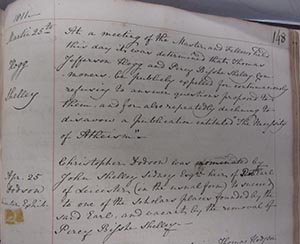

Less than six months, however, after Shelley properly took up residence in Univ, we come to the moment in his life which has become so notorious, when he and Thomas Jefferson Hogg were expelled from the College on 25 March 1811 (image Ref. UC:GB3/A1/2 fol. 148r).

It has long been noted that Shelley was not actually expelled for writing his notorious pamphlet The Necessity of Atheism, but for “contumaciously” refusing to answer questions about it. Hints from Shelley’s own letters at the time suggest that, if he had chosen to deny authorship, the College would have been content to draw a line under the affair.

As a symbol of Shelley’s and Hogg’s expulsions, their names were ceremonially crossed out from the Buttery Book (image Rec. UC:BU4/F/81).

Life in the College then resumed as normal. If we look again at the photograph of the entry from the College Register above (image Ref. UC:GB3/A1/2 fol. 148r), we can see that, just below the account of Shelley’s expulsion, Sir John Shelley Sidney has had to nominate another Leicester Scholar after his nephew’s “removal”.

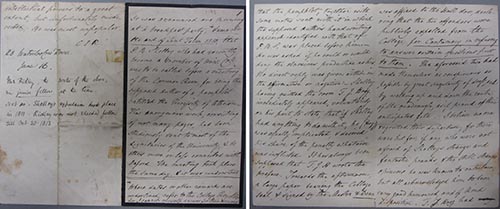

We have in the archives an interesting eyewitness account of the expulsion from Charles John Ridley, son of a Northumberland baronet who had come up in 1809, and who would be elected a Fellow in 1813, staying in post for forty years. He was a most properly conventional young man, and his memories undoubtedly reflect what Shelley’s less radical contemporaries made of him and Hogg.

Ridley remembered both men well, and the moment of their expulsion. Years later he set down this vivid little account of the events of 25 March 1811 (image Ref.:UC:GB3/A1/2)

Ridley’s lively account is worth reading in full, and a transcript of it may be found in the accordion section “The Sending Down Of Shelley – An Untitled Memoir By Charles Ridley” below. He is a good witness, not just because of his memories of Shelley and Hogg and the day of their expulsion, but also because, when he became a Fellow, no doubt Ridley heard tales of that fateful Governing Body meeting from some of the Fellows who were present.

The Sending Down Of Shelley – An Untitled Memoir By Charles Ridley

Perhaps people at Univ in 1811 hoped that, after the expulsion of two such rebellious spirits, they would quickly be forgotten, and that would be that. They were very wrong. Just how wrong will become clear in next month’s Treasure.

Further Reading

Robin Darwall-Smith, A History of University College Oxford (Oxford, 2008), pp. 339-42.

Published: 17 June 2022

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.