1864: The students are revolting (and so is the food)

Fig.1: Title page (UC:P41/N/1–2)

In the archives is a pair of copies of a very unusual document: a petition submitted to the Master and Fellows by a group of students (UC:P41/N/1–2), bearing the title page seen in Fig.1.

This petition, as will become clear, is arguably the first documented example of serious student protest at Univ. It is divided into three sections: “Reductions in Expenses”, “Improvement in Hall”, and “Miscellaneous”.

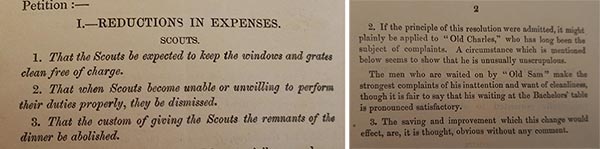

The first section, “Reduction in Expenses”, was concerned about aspects of the payment of servants, and other College expenses (Fig.2, below).

The students even single out particular scouts, like “Old Charles” and “Old Sam”, for their incompetence or even dishonesty (Fig.2, below).

There was especial concern that scouts ordered for every fresher a collection of brushes, mops, pails and brooms to keep their rooms clean. The freshers were certainly charged for these items, but the students claimed that they very rarely saw them, and hinted that the items were often promptly resold to the ironmonger, making a little extra money for the scouts.

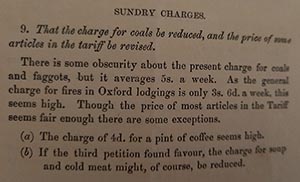

There are also complaints about the costs of coals, and some food and drink (Fig.3).

The second section, “Improvement in Hall”, sets out the perceived deficiencies of the catering arrangements there, be it the cost of beer, the over-catering, or the terrible standard of food. This section is worth quoting in full, and needs little comment (see Gallery 1, below).

The “Miscellaneous” section requests a tightening up of regulations about sending messages, and about the layout of battels.

The petition is signed by four students, John Douglas Walker, Alfred Robinson, Richard Crawley, and Charles Bill.

Gallery 1

It is an astonishing document: in it, the students of University College tear into almost every aspect of the domestic administration of the College, and what they perceive as their poor treatment by its servants. It also suggests a very serious breakdown in relations between students and servants.

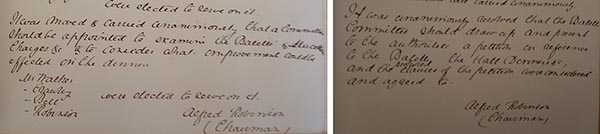

The pamphlet is undated, but another document in the archives has more to report. There was a debating society at Univ in the 1860s, and at the back of one of its minute books (ref. UC:O12/A1/2 – see Fig.4, below) is a section titled “College Meetings”, which seems to be a distant precursor of JCR meetings and ran from 1863 until 1864. Alfred Robinson chaired the meetings. These show that, at a meeting of 8 February 1864, it was agreed “that a Committee should be appointed to examine the Batells and Miscellaneous Charters &c & to consider what improvements could be effected on the dinner.” The meeting voted that Walker, Robinson, Crawley and Bill form that committee.

The Batells Committee worked fast. At the next meeting, on 2 March 1864, they were able to submit a report, which Walker read out for them. The members of meeting liked what they heard, for they voted unanimously that the Battels Committee present a petition to the College authorities.

Fig.4 – Left, Motion of 8 February 1864 (from UC:O12/A1/2). Right, Motion of 2 March 1864 (from UC:O12/A1/2) – click for larger image

Clearly then, this printed petition was the result.

What, then, had gone so wrong, and were the students’ claims justified? Perhaps the central problem was the way that College servants were paid in the 1860s. There had long been a tradition that the College would pay its servants a certain amount in wages, but that the servants then had the right to earn more on the side through “perquisites” – little extra charges which they could themselves request, or be expected to earn. Indeed, it is a somewhat moot point just how much money the more junior servants did receive from the College

The students felt that this system was being abused, be it through the dodgy reselling of brushes and brooms, or, more seriously, the matter of “remnants”.

“Remnants” or “remains” was the long-established tradition that, after Formal Hall, any food left over was a perquisite for the kitchen and serving staff, either to consume themselves, or sell on at their own profit. The students suspected that this tradition was open to abuse: it would be tempting to serve far too much food at Hall, but still charge students for it all, and then be able to take away a great pile of food afterwards which the students have paid for. This certainly seems to lie behind the students’ protest at the servants so ostentatiously hovering around the entrance to Hall at the end of dinner, eager to rush in and claim their rights, as well as the excessive amounts of cheese and butter.

These were serious matters, and it cannot have been easy for the students to resolve to broach them with the Master and Fellows. However, they were very fortunate in having some rather remarkable students to represent them, for all four members of the Batells Committee are worth exploring in their own right. Portraits of all four can be seen below in Gallery 2.

James Douglas Walker came up in 1860, and got a Third in Classics in the spring of 1864, so was deep in his Finals revision when drawing up the petition. He was called to the Bar at Lincoln’s Inn, and spent the rest of his life as a barrister. He became a QC in 1891, and was appointed Treasurer of Lincoln’s Inn in 1913. He also took a serious interest in the history of the Inn, writing substantial prefaces for four volumes of transcripts of the minutes of its Council, known as the “Black Books”. He died in 1920.

Alfred Robinson also came up in 1860 and read Classics, but he was of a rather more academic bent than Walker. He got a First in Classics in the spring of 1864, but then that summer also sat Finals in Maths and Physics, getting a Second. An academic career was clearly his for the taking, and later in 1864 he did become a Fellow – but of New College rather than Univ. Until the reforms of the 1850s, only former pupils of Winchester College could be elected Fellows of New College, and Robinson was one of the first non-Wykhamists to be elected to a Fellowship there. Nevertheless he thrived in his new home, becoming Bursar in 1875. Historians of New College are in no doubt that Robinson played a central role in the modernisation of the College. He was certainly highly regarded there: after his early death in 1895, a grand entrance tower to New College was erected in Holywell Street and named the Robinson Tower in his memory. As it happens, the records of the 1860s University College Debating Society were found among Robinson’s papers at New College, and later kindly transferred to us.

Richard Crawley came up in 1861 and also read Classics, getting a First in his Finals in 1865. Like Alfred Robinson, he then migrated to a Fellowship elsewhere, in his case becoming a Fellow of Worcester College. He was again called to the Bar at Lincolns Inn, but due to ill-health he never practised. On the other hand, he won a reputation as a poet and translator: in particular his translation of Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War was highly regarded, and remained in print long after his death. He died in 1893, and there is an entry for him in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

Charles Bill came up in 1861, and got a Second in Jurisprudence and Modern History in 1865 (at this time, these two subjects were combined). But he also got a Blue in the first Oxbridge Athletics competition in 1864. On going down, he was called to the bar at Lincolns Inn, but then travelled around the British Empire, and in 1892–1906 was Conservative MP for the Leek Division of Staffordshire. He died in 1915.

Gallery 2

In short, these are four young men who all went on to distinguished careers in different fields. It is also striking that three of the four signatories all trained as barristers. One feels that the junior members of the College had a very good idea of who among them would be their best representatives before the Governing Body.

But, you may well ask, did the Governing Body listen? It is pleasing to report that they did. As early as 19 March, they agreed: “That in consequence of the complaints against the Cook on the part of the Fellows & other members of the College, it be represented to him that unless there is considerable improvement during the ensuing term the College will be obliged to look out for a successor.” On 21 March they agreed “that for the two ensuing Terms no Table Beer be brewed in College, but that a light Table Beer be got in from some Brewery.” In March 1864, they also discussed ending the system of remains, and finding a way of compensating the servants accordingly, but agreed to investigate further.

Then on 21 March 1865, the Master and Fellows brought in some far-reaching reforms to the domestic administration of the College. Now all remains of food went straight back to the Kitchen, and the Cook would pay the College £60 for such remains. Those servants who had previously enjoyed the right to remains, namely the Bedmakers (i.e. Scouts), Porter, Kitchen woman, and the Under Butler, would now cease to benefit from them, but in compensation would have their wages raised by £7. They did allow for the remains of beer left in the Hall to be divided as before, but now only one servant would be allowed to enter the Hall to collect it – no more indecorous jostling around the entrance.

The College accounts from the 1860s suggest that the servants were indeed being paid in a more transparent way, and would be in less need of perquisites to top up their wages. It is true that perquisites took a long time to disappear – it is claimed that, even in the Edwardian period, wealthy undergraduates might leave the contents of their wardrobes to their scouts on going down – but the worst abuses faded away.

One will never know if, thanks to these reforms, the servants’ net salary decreased or stayed the same, but at least they were receiving a larger fixed salary. Later on in the century, the College started other positive initiatives like a Pension Fund for servants.

Fig.5 – H. Neville, John Hill’s scout (UC:P4/P/1)

At the same time though, a subtle change in how servants were perceived is at work. In the middle of the century, College servants did not generally enjoy a good reputation: both in fact and in fiction, in such novels as Verdant Green, they were portrayed as fleecers of the men they served. Even at the time, however, this picture may have been overdrawn. An older contemporary of our student petitioners, John Hill, who came up in 1859, saw fit to include in his photograph album images of the head porter and this one of his scout, H. Neville (Fig.5).

These are the earliest known photographs of College members of staff. Neville was almost certainly among those who were attacked in 1864 for being a bit too eager to earn a bit on the side, but John Hill would not have included his photo in his album if he did not like him.

By the end of the century, however, College servants were enjoying a very different reputation: relations between servants and students were a great deal friendlier and deeper. Now the College servant of fiction, like Venables (“Venner”) in Compton Mackenzie’s Sinister Street, could often be a wise counsellor whose advice should be taken seriously.

Interestingly, Univ’s troubles with servants in the 1860s were not unique. There are similar situations reported in Lincoln and Christ Church, and Magdalen had carried out similar reforms to Univ’s a decade earlier. It is clear, then, that there was a growing awareness that College staff deserved to be treated – and paid – in a different way from before.

This petition of 1864, then, is a fascinating document on so many levels. Not only is it the earliest definite example of a concerted activism among Univ’s students, but it also sheds light on the pay and conditions of its staff, and it even led to major reforms to improve their conditions.

Further Reading

Robin Darwall-Smith, A History of University College, Oxford (Oxford, 2008), pp. 381–4.

On Alfred Robinson’s role at New College, see H. B. George, New College 1856–1906 (Oxford, 1906), pp. 7 and 56–7, and A. Ryan, “Transformation, 1850–1914”, in J. Buxton and P. Williams (eds.) New College Oxford 1379–1979 (Oxford, 1979), pp. 85–6.

Published: 23 February 2022

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.