Der Geist von Canterville

Fig. 1: half title page

Since its original publication, Oscar Wilde’s story The Canterville Ghost has been turned into operas, reprinted numerous times in many languages, turned into a graphic novel and picture books, adapted many times for TV, film, and the music hall, released as audio books and recorded for the radio, and even been the inspiration for heavy metal songs. The Canterville ghost was the first of Wilde’s stories to be published (appearing in two parts in February and March 1887 in a magazine called The Court and Society Review) and has continued to delight readers, viewers and listeners to this day. In the humorous tale, an American family move into an English manor house haunted by the previous resident who had been starved to death within the walls as a punishment for a dreadful deed.

This Treasure travels back to 1897, when the ghost story was first translated from English into German. The book, now titled, Der Geist von Canterville, and the first of Wilde’s works to be translated into German, was printed in Munich in a very limited edition of 60 copies. The books were never intended for sale, but were instead circulated privately amongst friends of the translator and publisher, with one copy being deposited in the Bavarian State Library, the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek. The only known copies in the UK are both in Oxford: our copy and another at the Bodleian Library.

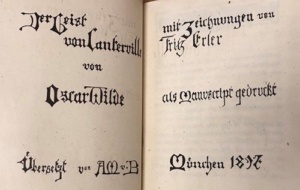

Fig. 2: title page

It might sound unusual for the Victorian era, but the translator was a woman, identified on the title page only by her initials, A.M. v. B. Walter Ledger, who was both compiling a bibliography and collecting Wilde’s works, was alerted to the existence of this translation, probably through an unauthorised reprint that was published in 1905. Somehow, Ledger connected the book with Max von Boehn (a writer on dolls, puppets, and automata) and wrote to him in 1909. It is worth noting Ledger’s tenacity here, as finding a stranger’s address in another country in the early 20th century was a great deal more difficult than it would be even today. Through the subsequent correspondence, Ledger confirmed that it was Anna Marie von Boehn, Max’s sister, who had translated the ghost story for German readers.

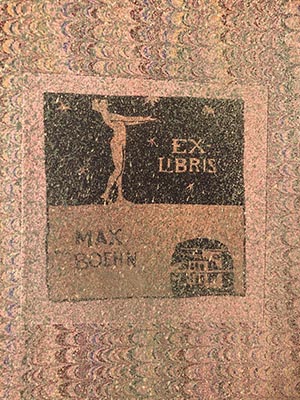

Fig.3: Max von Boehn’s bookplate

Although Walter Ledger wanted a copy of the scarce book for his collection, in 1909 the von Boehns would only agree to lend him a copy so that he could accurately describe it for the bibliography he was compiling. He notes therein: “The author is indebted to Herr Max von Boehn, who has lent his copy for that purpose, for the opportunity of describing this interesting and beautiful little volume.”

When Ledger hadn’t managed to acquire a copy of Der Geist von Canterville by 1923, he ventured another letter to the von Boehns, optimistically using the same address. In a letter to his friend, Christopher Millard, Ledger says of his request to buy Max von Boehn’s copy, “He may be glad to do so now – that is if he’s alive & my letter reaches him.” Against the odds, the letter arrived safely and Max von Boehn replied, as Ledger had hoped, explaining that the brother and sister’s straitened circumstances meant that they were willing to sell the book for £10 English pounds.

It doesn’t speak well of Ledger that he appears to be profiting heartlessly from the hyperinflation that the German people were suffering under the Weimar Republic in 1923. With German banknotes almost worthless, the possibility of selling a valued possession for English pounds seems, sadly, to have been too good an offer to turn down. Ledger’s comment later in his letter to Millard makes it plain that he was fully aware of the situation in Germany: “I would give him half a million marks for it!!”

When Ledger received the book, it had been beautifully bound in half red leather with marbled paper used on both the cover and as end leaves. Max von Boehn’s striking bookplate has been pasted inside. Both the bookplate and the end leaves have been coated in a thin layer of gold ink. It’s possible that the bookplate was also designed by Fritz Erler, who was known to take bookish commissions.

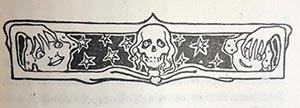

Fig. 4: illustration

Curiously, the illustrations in this edition take a darker tone than those usually associated with The Canterville ghost. The illustrator was Fritz Erler (1868-1940), a well-known painter, graphic, and interior designer who came to be associated with the propaganda posters he designed during World War I. This head-piece probably represents the twins who feature in the story.

Fig.5. Colophon

Another unusual feature of the book is that the colophon, which gives information about the publication is printed so that it reads from the lowest line upwards. In his bibliographical notes, Ledger translates:

This book was printed for friends only, in sixty copies of which one on silk, and another on vellum. Mr Fritz Erler was kind enough to design the title-page and the illustrations; it has been printed by Brügel & Son of Ansbach, the whole expense was defrayed by the translator’s brother.

Even though we might not agree with Ledger’s methods in acquiring this little book, it’s hard to disagree when, in his bibliographical notes, he describes it as ‘an exceptionally artistic specimen of bookmaking [that] will hold a foremost place in the esteem of collectors.’

Ross f.101: Wilde, Oscar, Anna Marie Von Boehn, and Fritz Erler. Der Geist Von Canterville. München: [C. Brügel & Son], 1897.

Fig.6. Binding

Bibliography:

Erler, Fritz. Grove Art Online. Retrieved 14 Jan. 2022, from oxfordartonline.com

Widdig, Bernd. Culture and Inflation in Weimar Germany. Weimar and Now ; 26. Berkeley, Calif. ; London: University of California Press, 2001.

Published: 18 January 2022

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.