Oscar Wilde abroad

Walter Edwin Ledger (Ross d.209)

Thanks to the generosity of book-collector Walter Ledger, Univ Library owns an outstanding collection of over 1000 Oscar Wilde-related items. The Happy Prince and Other Tales is well represented in the collection: Ledger acquired the British and American first editions, multiple English-language reprints, and the earliest translations into German, Czech, French, Dutch, Finnish and Russian.

This Treasure will focus on the translations, exploring what they can tell us about the reception of Wilde in different cultures. The translations also offer an excellent opportunity to view the work of women, who are often underrepresented in records of Wilde’s era.

A facsimile exhibition of these rare books will be available to view in the Swire Seminar Room from 26 November, 2018 until the start of Hilary Term, 2019.

Ross e.123 (British 1st ed.), plate 1

Background to The Happy Prince

When the original version of The Happy Prince was published in May 1888, Wilde’s career was flourishing. As well as being a prize-winning poet, he held a prestigious job as editor of The Woman’s World magazine, where he advocated a more modern outlook on the role and interests of women. The Happy Prince seemed to cement his reputation as one of the literary greats of the future, earning him ecstatic reviews. The public disgrace and prison sentence that Wilde would endure in the 1890s, because of his then-forbidden homosexuality, were not yet on the horizon.

Indeed, Wilde seemed to be happily married to Constance Lloyd, with whom he had two sons. The title story in the collection, The Happy Prince, had been invented with his eldest son, Cyril, in mind, during a visit to Cambridge in 1885. The other four stories had quickly followed in a phase of great imagination and productivity. Although marketed as children’s stories, their dark themes and harsh life lessons can make a strong impact on readers of all ages.

The stories

Here is a quick summary of each story:

The Happy Prince – A beautiful bejewelled statue of a prince asks a swallow to pick off his jewels and give them to the poor and needy. The Prince even donates his ruby eyes, making himself blind. The swallow puts off migrating out of friendship for the Prince, but then dies of cold. The Prince’s leaden heart breaks and the townspeople demolish him.

The Nightingale and the Rose – A student longs for a red rose to give the girl he loves. A nightingale overhears the student’s lamentations and decides to help. The winter is so cold that no red roses can grow naturally, but one rosebush says he will be able to create one if the nightingale is willing to dye it with her heart’s blood. She stabs herself with a thorn and sings all night while her blood ebbs away. The next morning, the student picks the red rose and takes it to his girlfriend, but she throws it in the gutter and says she would rather have jewels.

The Selfish Giant – A mean and greedy giant does everything he can to prevent local children from playing in his garden. The Spring is so upset by the lack of children that she stays away from the garden, letting eternal Winter freeze all the flowers away. Eventually, the giant relents and allows the children back in. The Spring returns and the children become the giant’s friends until he dies.

The Devoted Friend – An innocent man named Little Hans runs constant errands for the local Miller, who he believes is his best friend. The Miller talks eloquently about the principles of friendship, but never does anything to repay Little Hans’ endless kindnesses. One freezing night, while fetching the doctor to tend to the Miller’s son, Little Hans dies. The story is narrated by a Linnet, who wants to teach her neighbour the Water-Rat to be less selfish.

The Remarkable Rocket – A group of fireworks chat while they wait to be let off at a royal wedding. One rocket arrogantly insists that he has a far more refined and sympathetic nature than the others. His crocodile tears of “sensitivity” make him too wet to be let off, so he is thrown into a ditch. He lectures the animals in the ditch on his own superiority, without much effect. Eventually, two boys come along and put him on a fire to boil their kettle. The boys fall asleep and miss the Rocket’s explosion, but the Rocket dies still believing he is a genius and a success.

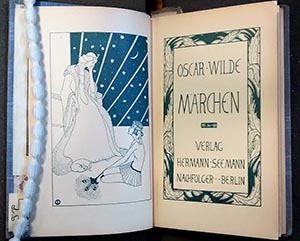

Ross f.97

German

The German translations are the earliest in Ledger’s collection, suggesting that Wilde made it to the land of the Brothers Grimm relatively quickly. The stories in The Happy Prince are set in a “fairy-tale” world – animals talk, statues come to life, giants roam the Cornish countryside – so it is understandable that they were welcomed by publishers in a country where magical fables were ingrained in children’s upbringing. (The work of the Brothers Grimm was only the tip of the iceberg in a centuries-long tradition of oral fairy-tale-telling.)

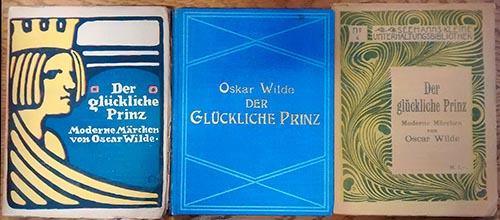

Ross f.98-100

The publishing house Hermann Seemann Nachfolger went so far as to retitle Else Otten’s translations Der glückliche Prinz: moderne Märchen (The Happy Prince: Modern Fairy Tales) and then, in a slightly later edition, simply Märchen (Fairy Tales). The presence of several editions shows that the stories excited audiences; the later Märchen volume has specially commissioned illustrations, possibly a sign that enough copies had been sold to allow for some extra investment. Fairy tales can be brutal as well as charming, and Wilde’s stories do not appear to have been adapted or abridged, indicating that German children were not put off by their darker side.

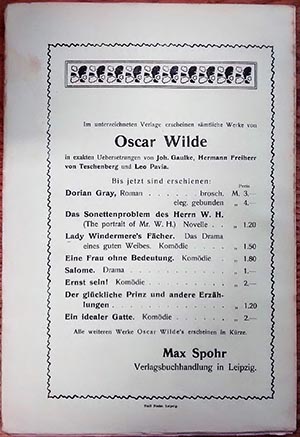

Ross e.342 (back cover, showing list of works in the series)

The publisher Max Spohr took a different approach. His volume Der glückliche Prinz und andere Erzählungen (The Happy Prince and Other Stories), translated by Johannes Gaulke, is from a series of exakten Uebersetzungen (“exact translations”) of Wilde’s complete works. The series suggests that Wilde himself was becoming known in Germany and that he carried interest and appeal for the public. The translator’s flowery style is more suitable for sophisticated older booklovers. However, it is interesting to note that despite the claimed fidelity of the translations, some liberties were taken with the titles of other works: The Importance of Being Earnest became Ernst sein! (Being Earnest!), which presumably sounded jollier to a German audience.

Ross e.342 Wilde, O. and J. Gaulke (tr.) (1903) Der glückliche Prinz und andere Erzählungen. Leipzig: Max Spohr.

Ross f.97 Wilde, O. and E. Otten (tr.) (1904) Märchen. 2nd ed. Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger.

Ross f.98 and 99 Wilde, O. and E. Otten (tr.) (1903) Der glückliche Prinz: moderne Märchen. Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger.

Ross f.100 Wilde, O. and E. Otten (tr.) (1903) Der glückliche Prinz: moderne Märchen. 2nd ed. Leipzig: Hermann Seemann Nachfolger.

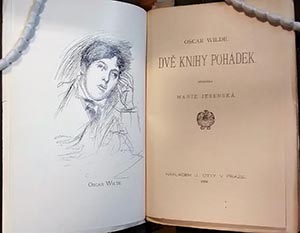

Ross e.400

Czech

The Czech translations are further examples of how publishers from one country can react quite differently to texts. J. Otty’s published version of Marie Jesenská’s translation seems designed for serious English-literature enthusiasts: it begins with a ten-page biography of Wilde and full list of his works, before moving onto the full texts of both The Happy Prince collection and its 1891 follow-up, A House of Pomegranates. Once again, the “fairy-tale” aspect is foregrounded: the book’s title, Dvĕ knihy pohádek, means Two Volumes of Fairy Tales).

Ross f.108

The publisher Edvard Leschinger, however, chose to have translator V. A. Jung abridge the Happy Prince stories quite extensively and omit The Nightingale and the Rose. This translation was published as part of a series for the very young, so perhaps Jung and Leschinger were concerned about the suitability of what is arguably the most disturbing tale in the collection. At the core of The Nightingale and the Rose is a painful, misguided suicide.

Ross e.400 Wilde, O. and M. Jesenská (tr.) (1904), Dvĕ knihy pohádek. Prague: J. Otty.

Ross f.108 Wilde, O. and V. A. Jung (tr.) (1904), Šťastný princ. Sobecký obr. Vĕrný přítel. Znamenitá raketa. Prague: Edvard Leschinger

French

The French translation is an anomaly: it represents not so much a rebranding of Wilde’s work as an embarrassing misunderstanding. Translator Albert Savine and publisher P.-V. Stock, who had previously worked together on French versions of Wilde’s Intentions and The Picture of Dorian Gray, decided to combine the author’s more recent output into one large volume. Le Crime de Lord Arthur Savile not only includes the titular novella (Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime), but a selection of Contes and Nouvelles (tales and short stories). The Contes are the five stories from The Happy Prince, rearranged so that The Devoted Friend and The Remarkable Rocket come first instead of last. The Nouvelles, unfortunately, are fakes. The art of Wilde-forgery had flourished as the author’s reputation grew, and a publisher grappling with the challenges of doing business in a foreign language could easily be caught unawares.

Ross e.231

However, collector Walter Ledger was able to set the record straight. On 5 October 1905, he wrote to a French contact of Savine’s to ask if the Nouvelles could be replaced with the three genuine Wilde stories that had accompanied the first British edition of Lord Arthur Savile’s Crime. He also suggested that it would be “advantageous” to return the Happy Prince stories to their original order. On 10 October, he posted his own rare first edition to France to aid Savine in his work.

Sadly, there is no evidence that a revised version of Savine’s translation was ever published, but Ledger’s swift response to the error shows how assiduous he was in trying to preserve Wilde’s literary legacy.

Ross e.231 Wilde, O. and A. Savine (tr.) (1905), Le crime de Lord Arthur Savile. Paris: P.-V. Stock.

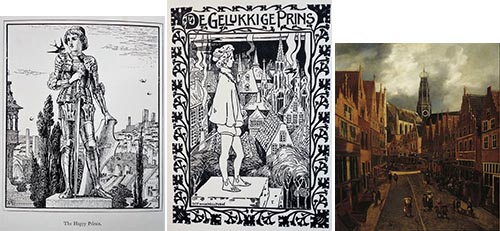

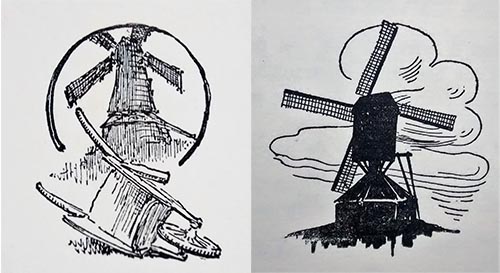

Dutch

The Dutch translation is a visually striking example of foreign publishers’ refashioning of Wilde. Some of Gust. van de Wall Perné’s illustrations seem to be “Dutchified” versions of Walter Crane and Jacomb Hood’s originals. For example, the statue of the Happy Prince still gazes out over a city, but instead of the towers and archways of a generic fairy-tale land, he sees pointed roofs and church spires in historical Dutch style. His clothing is no longer a knight’s shining armour but the cap, cloak and breeches of a traditional Dutchman.

(L-R) Ross e.123 (British 1st ed.), plate 1 – Ross d.75, p. 6 – Painting of Haarlem, Netherlands, by Nicolaes Hals (© WikiCommons)

At the end of The Devoted Friend, when the Miller selfishly complains that he cannot give away his wheelbarrow because the recipient has died running errands for him, Crane and Hood’s vignette of a windmill and wheelbarrow becomes one large windmill. It is as if van de Wall Perné has zoomed in on the most traditionally Dutch aspect of the picture.

Ross e.123, p. 85 – Ross d.75, p. 62

Linguistically, Marie van Oosterzee’s translation provides a useful record of how Dutch children might have been taught to speak at the time. The remnants of a Germanic case system, now extinct in Dutch, are regularly used, while some of the vocabulary is unrecognisable today. Dutch is a language that ages fast. Therefore, despite this book’s visual beauty, it would not be very accessible to modern children.

Ross d.75 Wilde, O. and M. van Oosterzee (tr.) (1906), Moderne sprookjes. Baarn: Hollandia-Drukkerij.

Ross e.396

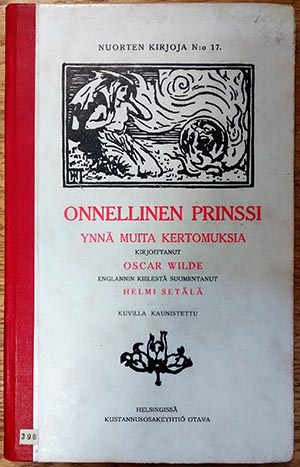

Finnish

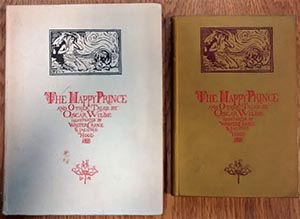

The English-language Happy Prince’s influence on this translation is immediately apparent. The front cover is a near-replica of the British and American equivalents. Crane and Hood’s original illustrations appear both here and inside the text, allowing readers to engage with the book almost as Wilde himself would have known it.

Publisher Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava’s approach displays openness to foreign cultures, especially as translator Helmi Setälä’s name is highlighted in almost as big a font as Wilde’s. Until recently, it was quite common in English-speaking countries to underestimate the translator’s labour and to name them in small print or not at all, so the Finnish choice shows a refreshingly early acknowledgement of the challenges of the craft.

Ross e.123 (British 1st ed.) and e.129 (American 1st ed.)

However, this translation is not perfect. Readers can spot the occasional grammatical error, which could imply that Otava rushed the book’s release, for convenience’s sake or as a cost-cutting tactic. Such a strategy would probably not work today, as the imitative design would have to be extensively negotiated to avoid copyright infringements.

There is one important difference between the translated text and the original: The Nightingale and the Rose and The Selfish Giant have been swapped around. The reasons for this are not clear. It is conceivable that, like the Czech V. A. Jung, Helmi Setälä shied away from the dark themes of The Nightingale and the Rose and wished to reduce its prestige within the collection. The Finnish translation was, like Jung’s Czech version, produced as part of a series for young readers.

Ross e.396 Wilde, O. and H. Setälä (tr.) (1907), Onnellinen prinssi ynnä muita kertomuksia. Helsinki: Kustannusosakeyhtiö Otava.

Ross e.416 and e.417

Russian

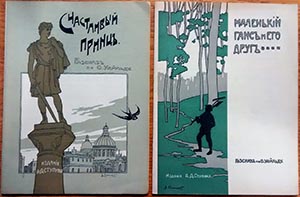

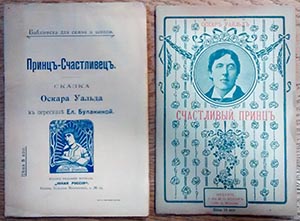

Although the Russian translations were the last to be published, there are several of them, suggesting that Wilde’s work pleased readers when it finally reached this other bastion of the fairy-tale tradition. Their appeal was, however, not without heavy input on the part of translators and publishers. More than half of the stories were cut, and the two that remained were abridged into pamphlets, cheap to produce and easy for children to handle.

The two stories were The Happy Prince and The Devoted Friend, with the former being much more popular among translators, three of whom worked on it as opposed to just one on the latter. The title of The Devoted Friend was changed to маленький гансъ и его другъ (Little Hans and his Friend), removing the irony in the fact that the “friend” character is not actually devoted at all. The sobering, instructive plight of Little Hans is implicitly foregrounded over Wilde’s sly humour.

Ross e.419 and e.420

These translations were released in very small print runs, as was typical in a country whose publishing industry had been strictly controlled until only a couple of years beforehand. The children who obtained them were a privileged minority, and surviving copies are extremely rare. Elena Bulanina’s 1908 translation of The Happy Prince, released as a supplement to Юная Россия (Young Russia) magazine, was one of only five copies; Ledger’s appears to be the only copy available in a library today.

Ross e.415 and 416 Wilde, O. and I. P. Sakharov (tr.) (1908), счастливый принцъ. Moscow: A. D. Stupin.

Ross e.417 and 418 Wilde, O. and I. P. Sakharov (tr.) (1908), маленький гансъ и его другъ. Moscow: A. D. Stupin.

Ross e.419 Wilde, O. and E. Bulanina (tr.) (1908), счастливый принцъ. Moscow: Iunaia Rossia.

Ross e.420 Wilde O. and an unknown translator (1908), Принцъ-Счастливецъ. Saint Petersburg & Moscow: T-va M. O. Vol’f.

With thanks to Chantal van den Berg and Reija Fanous for their helpful comments on the translations

Selected Bibliography

The translations and British and American first editions of The Happy Prince are held in the Library’s Robert Ross Memorial Collection. They can be requested for consultation by contacting the Library – E: library@univ.ox.ac.uk

A modern English-language edition of the stories from The Happy Prince and A House of Pomegranates can be borrowed from the Old Library at YHV/WIL.

Other resources at Univ Library (all available in the Old Library unless specified otherwise):

YAT/BEL Bellos, D. (2012), Is that a fish in your ear?: the amazing adventure of translation. London: Penguin Books.

YAT/STE Steiner, G. (1998), After Babel: aspects of language and translation. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

YHV/WIL,E Ellmann, R. (1997), Oscar Wilde. London: Penguin Books.

YHV/WIL,E (New Library Office) Evangelista, S. (ed.) (2015), The reception of Oscar Wilde in Europe. London: Bloomsbury.

YHV/WIL,M (New Library Office) Mendelssohn, M. (2018), Making Oscar Wilde. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

YHV/WIL,S Schmidgall, G. (1994), The stranger Wilde: interpreting Oscar. London: Abacus.

ZCK Garland, H. and M. Garland (eds.) (1997) The Oxford companion to German literature. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

ZCR Kahn, A. et al (eds.) (2018), A history of Russian literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

The letters from Walter Ledger to a French contact of Albert Savine’s are held by The William Andrews Clark Memorial Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

Published: 27 November 2018

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.