Mercator’s Atlas

This month’s treasure feature is on one of our early printed books, an atlas by Gerardus Mercator (1512–94).

The Mercator Projection

Mercator was a Flemish geographer and cartographer, known mostly for his attempt to represent the spherical earth as accurately as possible on a flat sheet of paper. Now called the Mercator projection, his system straightened out the meridian lines on a globe, meaning that land masses were stretched east-west, more prominently the further from the equator they are. To combat the way this deformed their shape, Mercator imposed a proportionate stretching along the north-south lines. This maintains the angles and shapes of countries, but has the unfortunate effect of distorting the relative sizes of land masses, meaning Greenland looks similar in size to Africa, whereas it’s closer to the size of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. To see how this works, a useful interactive map is available at thetruesize.com.

Mercator’s world map, published in 1569, was titled Nova et aucta orbis terrae descriptio ad usum navigantium emendate accommodate or “New and More Complete Representation of the Terrestrial Globe Properly Adapted for Use in Navigation” (Monmonier, 2004). The projection allows sailors to navigate following rhumb lines (or loxodromes), as these always appear on the map as straight lines, with the curvature of the earth taken into account. Mercator had found a way to transfer a 3D object onto a 2D plane.

Although Mercator is most famous for his projection, it does not actually feature in his atlas. Instead it was published separately, in 1569, well before the first volume of his atlas. The world map included in the atlas from 1595 is one produced by Mercator’s son, Rumold, using a pair of hemispherical projections (Monmonier, 2004, pp. 59-60).

The Atlas

Mercator’s Atlas was initially published in three volumes, released in 1585, 1590, and 1595. He had grand plans to make this a five-part work covering not only geography, but also astronomy, astrology and the history of creation (Krogt, 2015, p. 113). However, Mercator was never able to realise his plans for the atlas, and when the “complete” atlas was published in 1595 it contained only two parts: Mercator’s text on the creation of the world, and his geography. Judocus Hondius (1563-1612) bought the engraved copper plates for the atlas as part of Mercator’s estate in 1604, and in 1606 published his first edition, adding 36 new maps to Mercator’s original 100. These new maps included Spain and the Americas (Tunturi, 2016). This was so popular that the next year a new edition was published, and by 1633 there had been 14 editions of the Mercator-Hondius Atlas.

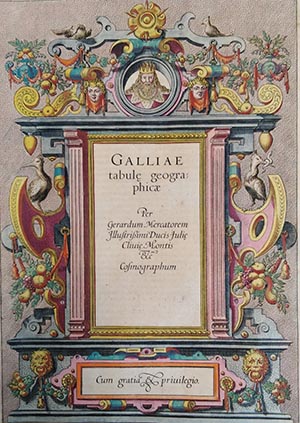

Gaul title page

Our copy of Mercator’s Atlas is missing its title page, which causes problems in identifying the publication date and edition number. We had previously believed it to be the 1607 edition. However, the volume contains an epitaph to Hondius, who died in 1612, suggesting a later publication date. We are currently attempting to identify which edition we have, which will involve comparing our copy with those held in other libraries, checking the text used, the layout, page numbers and signatures. On top of this, we will have to work out whether missing pages were cut from the volume after printing, or not printed in the first place. Unfortunately, due to the current pandemic, this research has had to be put on hold until the library reopens.

We received our copy of Mercator’s Atlas as a donation from an Old Member of the college, Leonard Digges (1588-1635). He was a poet and translator, and an early admirer of Shakespeare (Darwall-Smith, 2016). He donated a number of books to the college, all of which are still in our collection. The exact date of his donation is unknown, although it seems likely that it was sometime in the 1630s. Unfortunately, this does not help us date the Atlas, as we do not know how long it might have been in his personal collection before he donated it to Univ.

The Maps

The Atlas is divided into sections by country/geographical area, with each section preceded by a title page for the area, such as the one above for Gaul. The title page is then followed by supplementary text, in Latin, detailing a little of the history and points of interest relating to that country or region.

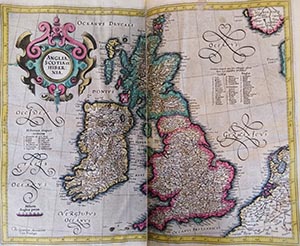

And then, in amongst the text, are the maps. Intricate and detailed, usually covering a double-page spread, and (at least in our copy) coloured throughout, these maps are impressive both as works of cartography and art.

Korea depicted as an island

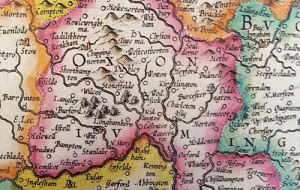

Mercator’s maps contain a stunning degree of detail, not just in depicting countries but also on a county level. For example, see the map of Oxfordshire at the top of the page.

In spite of the stunning accuracy which prevails through most of the atlas, there are nonetheless odd moments which provide amusement for the modern reader. For example, take the map left, which represents Korea as an island off the coast of mainland China! In some editions one of the maps of China does contain a note, in Latin, questioning whether Korea is an island or part of the mainland, and it will be interesting to see whether our copy contains this note, once we are back in the library after the lockdown.

And finally, because no map would be complete without an assortment of fearsome sea monsters and unusual birds, the atlas also features some wild and wonderful creatures. Although (disappointingly) none of Mercator’s maps contain unchartered areas marked “Here Be Dragons”, an assortment of charming creatures decorate the borders around text and areas of seawater. Below is a selection of some of these.

References

Darwall-Smith, R. (2016). Leonard Digges: Univ’s First Shakespearean. The Martlet, 5, 16-17. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from here.

Keuning, K. (1947). The History of an Atlas: Mercator-Hondius. Imago Mundi, 4, 37-62. Retrieved January 23, 2020, from jstor.org

Krogt, P. v. (2015). Gerhard Mercator and his Cosmography: How the “Atlas” became an Atlas. In G. Holzer, V. Newby, P. Svatek, & G. Zotti (Eds.), A World of Innovation: Cartography in the Time of Gerhard Mercator (pp. 112-130). Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. Retrieved from ebookcentral.proquest.comMonmonier, M. (2004). Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. doi:10.7208/chicago/9780226534329.001.0001

Tunturi, J. (2016, May). Cartographer’s experience of time in the Mercator-Hondius Atlas (1606, 1613). Approaching Religion, 6(1), 46-56.

Published: 7 May 2020

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.