Discovering Fire Island

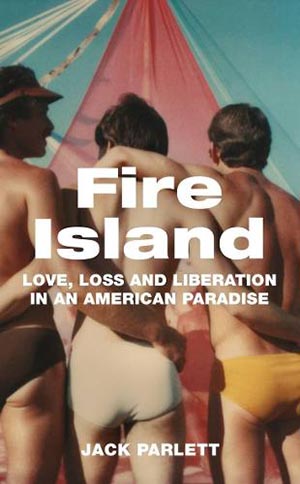

US edition (Hanover Square Press)

Fire Island is a long, thin strip of the land located off the south coast of Long Island, New York. Around thirty-two miles across in length, it is made up seventeen different vacation communities, which cater mostly to vacationers and families from the city and Long Island. A pair of communities towards the island’s middle, however, form a loud minority of two, offering – in theory, at least – a haven for queer people looking to get away from it all. The older of these communities, Cherry Grove, which dates back to the late nineteenth century, has been known as a queer destination since the late 1930s, when it first began attracting a curious crowd from the city who were euphemistically known as “theatre people”. Cherry Grove’s neighbour to the east, Fire Island Pines, was first constructed in the 1950s, and initially prided itself on its discretion as a more respectable and expensive alternative, with its beach mansions and marina, to the Grove’s ramshackle eccentricity. By the 1970s, however, in the years following the Stonewall uprising and the advent of the gay liberation movement, both communities were well-known as chic destinations on the map of queer America.

When asked about how I first became interested in Fire Island, I catch myself defaulting to the most obvious answer: that this research project grew quite logically out of my PhD thesis on cruising and queer sexual cultures in the work of several American poets, some of whom spent time there. In historical accounts of queer urban life in New York in the twentieth century, mentions of this place are certainly ubiquitous, its list of visitors a who’s-who of key cultural figures from the worlds of literature, art and entertainment. I became interested in Fire Island, then, because it seemed to crop up everywhere I looked, demanding closer inspection.

UK edition (Granta Books)

But the fuller and truer answer is that I first went to the island, in the summer of 2017, during an extended research trip in the second year of my PhD, in the spirit of something more than research. In part, I was looking to retrace the footsteps of my favourite poet, Frank O’Hara, who was killed in a dune buggy accident in 1966. Sat on the beach at the Pines at night, reciting one of O’Hara’s poems, I had no idea that I’d come to write a book about the history of the place, but I knew I was encountering something strange and memorable. When I came to start work on the project a couple of years later, I wanted to approach it in a way that wouldn’t efface what it felt and feels like to have an embodied experience in this space, nor to paper over the personal stakes of this project for me as a queer person who went there in search of the same thing as many others: pleasure, escape, inspiration.

After more trips to the island and time spent combing through the archives of some of its storytellers – including W.H. Auden and Patricia Highsmith, Edmund White and Larry Kramer – I began working on the full manuscript, just as the lockdown restrictions were introduced in March 2020. Confined indoors, like all of us, for several months, the process of writing the book felt like looking through a window towards a different world, a place of touch and togetherness, possibilities that had suddenly been rendered alien. It was as if I were trying to live vicariously through the writing, imagining myself back in a place that come to seem both real and imaginary, simultaneously close and distant. Conceiving of the island this way felt apt, somehow. As I began to realise, it has long been a place whose appeal depends upon fantasies both personal and shared, the collective desire to find a paradise, somewhere over the rainbow, the stuff of dreams and show-tunes.

Jack Parlett – Junior Research Fellow in English

But paradises are elusive, and the reality of the place is inevitably more complicated, its freedoms more limited than this idyllic reputation might suggest. As the novelist Toni Morrison once put it, “all utopias are designed by who is not there, by the people who are not allowed in.” Cherry Grove and the Pines are commercial vacation towns with unique infrastructures and high rents. They were built, in other words, to only accommodate so many, on the steadily eroding fringes of the Atlantic Ocean. That these communities have mostly been populated by white gay men and lesbians over the years speaks to the extent of the inclusion they have made possible. Today, artists and creatives in the Grove and the Pines are working towards a more inclusive future, seeking to make the island more accessible at a time when safe queer spaces for all are at a premium. Just as the wider queer community is no monolith, a coalition of the diverse communities within it, Fire Island means different things to different people, from old-timers to first-timers; those who live there – at least in the summer months – to those who have never been. But these are differences to learn from. In the process of writing this book, I’ve come to see Fire Island as a place that has much to tell us about community, belonging and queer identity.

Jack Parlett, Junior Research Fellow in English

Fire Island will be published on 26 May by Granta Books (UK) and 14 June by Hanover Square Press (US). Pre-order here.

Published: 10 February 2022