Istanbul to Sarajevo

Roger Short Travel Scholarships Report – Francesca Sollohub

Roger Short Travel Scholarships Report – Francesca Sollohub

I began my trip in Istanbul, then visited Plovdiv and Sofia, then the coast of Montenegro via Belgrade, and finally Sarajevo.

Istanbul – Sunday 7 July 2019

My hostel is in Galata, part of the old European district, and the balcony of my room looks out onto the Galata tower, built by the Genoese in the mid-fourteenth century as a replacement for the Byzantine Old Tower of Galata. On the skyline, dark against the dusky pink of sunset or at night glowing yellow, I can see two mosques and make a mental note to find out which is which so I can orient myself in the city. A little slice of the Bosphorus is also just visible.

I wandered up along İstiklal Caddesi (formerly Grande Rue de Pera in the days when the area was known for its European immigrant communities) looking for the Pera museum. My inability to follow simple directions meant I saw quite a bit of the street and its mix of modern chain shops, ice cream stalls, lottery ticket sellers and nineteenth-century mansions. I went accidentally into what turned out to be a Catholic church (Sent Antuan). Inside mass was being said in Italian – surprising, but why not – and I hung around for a bit avoiding the bouncers and enjoying the familiarity of the service and the language.

The Pera museum is small and contains exhibitions of artefacts from Istanbul’s various incarnations (tea and coffee pots, old weights and measures) and, most interestingly, paintings by Turkish and Western artists of ambassadors to and from the Ottoman court. It also has a room dedicated to Osman Hamdi, painter of the famous orientalist ‘Tortoise Trainer’ painting.

Monday 8 July

Monday 8 July

Travelling alone with no real object other than to explore makes very clear how much time there is in the day. On the one hand, I can do exactly what I like, when I like. On the other, I have no-one to sound ideas off or shake me out of decision paralysis.

It’s hot but I walk over the Galata bridge to the Sultanahmet side to see Topkapı palace. The palace is astonishingly beautiful, even with the crowds. In contrast to a French or English (or Czech or Italian etc.) palace, instead of a single enormous edifice surrounded by grounds, Topkapı is formed of several courts (the outer one having become Gülhane park) inside which are planted various buildings, kiosks and pavilions. So, the Sultan’s library has its own kiosk, as does the throne room and, of course, the Harem. And although there are no furniture or furnishings left inside the large rooms the exquisite tiles and mosaics remain; so that, instead of the cold, cavernous feeling of an empty stone castle, you can still imagine these rooms as somewhere to live, eat, sleep and talk. The Harem’s baths (hamam) are also brilliant interior design inspiration, if your tastes run to gold taps and white marble baths. My overwhelming impression is of blue – blue tiled walls, blue skies, blue glint of the Bosphorus from the terraces. Overwhelming is the word – the crowds, the beauty of the architecture and the art, the people taking pictures of themselves (and sometimes livestreaming themselves – what is that about?).

I spent a couple of hours reading in the shady peace of Gülhane Park, and bought a simit (sesame bagel) with cream cheese, then trudged back over the Galata bridge under a few light spots of rain. Locals were fishing off the bridge – I counted about ten rods on my side – but I don’t know how they’d catch anything off there. It might not be as filthy as the Thames but it is still a busy waterway with ferries and boats constantly passing under the bridge. The light was as lovely as ever. Maybe it is always like this.

Tuesday 9 July

Tuesday 9 July

I made my way over Galata bridge by tram, from Karaköy stop. I got off at Sultanahmet and thought of going to Ayasofya but seeing the queues decided to try the Archaeology museum first. This is in the grounds of Topkapı, next to Gülhane park – you can look out over the people lying around and talking from the terrace. I hadn’t realised that a significant part of the museum would be closed – the part with the Alexander sarcophagus, the exhibits on the history of the city and artefacts from different eras – but the rest was I think worth it. Sarcophagi from Anatolia with Roman and/or Phoenician influences; stele, which I think are gravestones, with inscriptions blessing and sometimes cursing the ill-intentioned reader; a skeleton and some actual mummies which always interest me. In the other section they had exhibits from the ‘ancient orient’, i.e. Middle East, including some dragon and bull friezes from the Ishtar Gate (I have seen parts of the gates before, in the Berlin Pergamon).

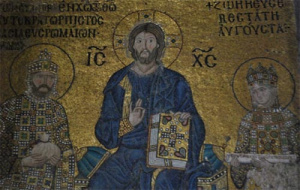

Then, after a can of peach juice and a couple of hours reading my book in the park away from the midday sun, I went over to see Ayasofya armed with my Istanbul Museum Pass and therefore able to skip the queue. Ayasofya is as beautiful and impressive and vast and all the other adjectives as people say. Not as much gold as in some other Orthodox churches which gives it (to me) a more sacred and dignified air. There are wide black and gold circles with the names of Ottoman sultans high on the walls, side by side with glittering mosaics of Christ and the Virgin Mary. It is a beautiful juxtaposition as they complement one another: the austere, graphic power of the Arabic calligraphy set against the kaleidoscopic colours of the mosaics. As with Topkapı, there is almost too much of Ayasofya to take in. I went up to the gallery where there are more mosaics and marble, and views from the open window casements of other mosques and minarets. The one blot is the scaffolding inside, which reaches up to the dome and blocks out a good part of the nave. Apparently this scaffolding has been somewhere inside Ayasofya for the past twenty years, so even though it moves around the interior is never completely clear.

I take the tram back to Karaköy and go to meet Victoria Short under the Galata tower. We walk around the corner to her flat, which as she tells me is in the first purpose-built apartment building in the city. From the rooftop, which looks out over the water, the city is astonishingly quiet – even Oxford is louder at night. Victoria tells me about how the city and neighbourhood have changed over the past fifteen years – the restaurant on the corner by the Galata tower that used to be a workmen’s café, all the boutiques and new coffee shops along Geldip and even the side streets which have appeared in the last ten years. Still, overall the area doesn’t seem to have changed too much, as down by the water there is apparently some kind of covenant on the land that prevents development, not that this is has prevented the new port project, whose cranes and halfway finished construction are visible in the dusk.

Wednesday 10 July

Wednesday 10 July

I head down to the docks to get the Haliç ferry over to the Western quarter where the Chora Church (alias Kariye Museum) is. It is lovely outside – the temperature has dropped at least five degrees since yesterday, and there is a fresh breeze as the ferry zigzags across the water before dropping me at Ayvansaray. The walk up to the church is steep and I take a meandering route which inadvertently/fortuitously passes by the old city walls. When I finally get to the Chora Church the entire exterior is covered in scaffolding – yes, this is a trend. Not only that, the paraclesion, which has some pretty unusual frescoes, is shut off, so I content myself with the mosaics in the nave and narthex. Even with about a third of the church off limits and the encasement in tarpaulin I am glad I came. The inside is pink and white, dusty pink stone forming the dome and white and grey marble cladding the walls. The marble slabs must have been cut in slices from the same blocks; having been arranged symmetrically, they produce patterns like the impression of ink on folded paper.

I wander down the hill through narrow, twisting streets. It feels much more like a normal neighbourhood than the city centre – there are lots of people going to and from the Wednesday market in varying levels of traditional dress. Women in black robes with veils pinned in front of their faces walk past the occasional bearded man in what looks like a seminary uniform of grey round hat and shirt, who I assume come from the Greek Orthodox college just down the hill. Then again they could easily come from a nearby mosque – unsurprisingly the Eastern Orthodox and Islamic costumes look very similar. I don’t feel as conspicuous here as I thought, although I am one of the few women in trousers and with my hair uncovered in what seems to be a more traditional or conservative area.

I walk further, down possibly the steepest street I’ve ever seen, Sancaktar Yokuşu Sokak, passing the Phanar Greek Orthodox college and possibly ruining a couple’s wedding photoshoot in the process. Before heading back to Galata I looked into the neo-Gothic Bulgarian church, St Stephen of the Bulgars. Here is the gold and baroque excess so happily missing from the older Byzantine churches. I take the ferry back from Fener, a couple of stops closer than the one I took on the way out.

When I get off the ferry in Karaköy it’s only 5.30pm or so and the evening air is light and cool by the pier. There are a couple of men fly fishing off the waterfront, surround by increasing numbers of lithe feline admirers waiting for fish. Neither fisherman is having much success, but after a while a thin wiry man shambles over to say hello and give some fisherman’s friendly advice, eventually taking over the rod for a bit. Everyone seems to know other here, on this collection of benches facing out over the water. This expert is clearly a fish-whisperer, as on the next cast he pulls out a small silvery fish which gets dumped unceremoniously in a bucket. Still not sure what they are going to do with these fish – later on another fisher throws some to the audience of cats and seagulls, so maybe it’s just the fun of standing at the water’s edge and seeing what it will yield. Turkish anglers are clearly the same disciples of futility as their English cousins. I stay there watching them and reading a book on Constantinople by Philip Mansel (recommended to me by Victoria) until about 8pm when it starts to get cold.

Thursday 11 July

Thursday 11 July

The weather breaks and it rains heavily all morning, so I make my first stop the Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts near Ayasofya, which gives a good overview of various eras and dynasties in Islam and Ottoman Turkey. There’s everything from ceramics and tiles to illuminated books – I really like the old Korans with the very upright script (kufic?) from the 9th century. There are some vast carpets in the final museum of the museum, wide enough to cover an entire floor.

As it is still grey and overcast when I leave the museum, I make my way over to the Basilica cisterns. They’re dark and damp, reminiscent of natural caves I’ve visited. The most visually arresting part of the cistern is in a corner where two Medusa heads being used unceremoniously to support two of the columns and looking fairly non-plussed by this reversal of fortune.

I get to the Blue mosque just in time to go inside before the 4.45pm afternoon prayers. The interior is beautifully tiled with blue, white and green, with deep red carpet underfoot. Although it’s a huge building, tourists can only walk in a small part so after about ten minutes I head off to the mosaic museum, reached by leaving from a side door in the mosque complex and walking through a bazaar. It’s a small museum but well put together – there’s lots of information about the origins of the mosaics (from a 4th century Byzantine palace) and the excavation and conservation process (which basically involved sticking them face-up to a plastic film and then relaying them in panels on a specially-developed mortar). As always, there was a lot of 19th century conservation damage to undo before they could properly preserve the mosaics. My favourite mosaic: a monkey about to climb a palm tree with a bird in a basket on his back (I think he’s meant to be a date picker).

That evening I meet Victoria again for dinner, and on our way to the restaurant we drop into Soho House Istanbul, which is housed in a building that used to be the old American embassy, and before that the palazzo of an Italian banker which explains the cupid-laden frescoes and Italianate interior. After that we looked into the Grand Pera Hotel, a Galata institution that during WWII was host to spies and journalists sheltering in the high-backed armchairs. Over dinner we talk about the post 2011/Gezi Park crackdown and how this has affected nightlife in Galata. It has started to recover, but even today many of the restaurants are half-empty. Victoria also explained about the increasing desecularisation of Turkey, which is especially visible in Istanbul as it used to be so cosmopolitan.

Friday 12 July

Friday 12 July

It’s my last day in Istanbul, so I walk up to Taksim Square one last time, and on my way back I stop into the Dervish museum on Galip Dede street, which is mid-way through renovation but still has an interesting exhibition about the Dervish lodges, their history and musical tradition (which I’ve also been reading about in my Constantinople book).

As I still haven’t been to the Asian side of the city I take the ferry over to Kadıköy, landing near the old station where the Orient Express used to arrive. There isn’t much in the way of museums or sights (aside from a couple of Orthodox churches) so I just wander around the bazaar and enjoy being in a relatively tourist-free part of the city. At one of the crossroads in the bazaar there are four men playing Turkish songs – the crowd gathered around them joins in and requests numbers so I assume they must be folk or newer popular songs. At some point they’re joined by a couple of living statues, gold and silver, who I’d walked past earlier, which made for a slightly surreal scene.

Before I leave I sit on the quayside near the ferries, feet over the edge, looking at the lowering sun. There are hundreds of jellyfish pulsing gently in the green-blue water; a black cormorant beats its wings again and again and finally takes off from the water just enough to glide a few metres and then settle back into the slight swell of the waves. The light here really is wonderful.

Saturday 13 July

Saturday 13 July

I am leaving Istanbul. I wish I weren’t, but I won’t otherwise have time to see Plovdiv, Sofia, Sarajevo and meet my friend Sara (who is staying with her relatives in Montenegro), and make it to Prague in time to start my Czech course at the end of the month. Three weeks doesn’t seem long enough, and a week in Istanbul is definitely too short. It does give me a reason to come back, and I’m already making lists of where to go and what to see in Turkey next time.

We pass through fields of sunflowers, some with heads turned to the sun, others with head bowed and drooped, olive trees and the occasional village. The sky is light blue, the ground yellow ochre and the trees verdant. Crossing into Bulgaria there is a perceptible shift, as gradually hazy blue mountains creep onto the edges of the scene, and green trees and crops start to outnumber yellow fields. We pass through a few villages with red-roofed houses which are mostly run-down and dilapidated, donkeys, carts, and ancient looking rusted farm equipment littering the yards and paddocks. The plain is also punctuated with industrial chimneys which stand tall and thin in the middle distance.

We arrive in Plovdiv sooner than I expected and I find myself on the side of the road wrestling with my backpack at about 7pm. I plod along to the hostel down Boulevard Ruski, the town strangely quiet for a Saturday evening. The hostel is small but I would recommend it to anyone going through Plovdiv – Ginger House on ulitsa Preslav, with a very helpful and friendly owner. The other travellers invite me to join them in their homemade shopska salad, a Bulgarian speciality involving tomato, cucumber, pepper, parsley and white cheese.

Plovdiv – Sunday 14 July

Plovdiv – Sunday 14 July

There’s a free walking tour of Plovdiv run by a Bulgarian cultural non-profit called 365. After a week of taking myself places it is refreshing to have a guide to follow around, and although it moves quite slowly Plovdiv is so small that it doesn’t matter. About halfway through the tour a real storm comes over us, thunder and rain, and I get pretty soaked. It is hard to appreciate how pretty the Old Town is in this weather, but I try. The houses have a peculiar style that I haven’t really seen before – like a combination of German or Swiss wooden houses and renaissance Italian. They’re not particularly tall, two or three stories, which contributes to the village feel of the Old Town (especially compared to Istanbul, where even the old houses are high and narrow). In Kapana (the Trap), and old and now up-and-coming again district of bars, cafes and artists, the buildings have more of a central European style. Kapana used to be somewhere you could find anything you wanted, from the time of Byzantium until the 20th century. A fire in 1906 destroyed all the old wooden houses and shops which were piled on top of one another in a warren of intersecting streets (hence the name – it was easy to lose yourself in Kapana). It was rebuilt along the same principle of shop below, apartments above, in the 1920s in a style known (I think) as 1920s baroque. I quite like these buildings as there’s something Art Deco or even Bauhaus about the square lines.

To escape the rain I stop, sodden, into the Archaeological museum. It’s small but stuffed full of interesting and beautiful objects. The history of Plovdiv, known previously as Philippopolis, is fascinating and unites Thracian prehistory, the Byzantine and Ottoman empires and the Russian power struggle in later centuries. It is considered one of the oldest cities in Europe, with pottery found there dating from the 6th millennium BC – there is too much to go into here, but it’s useful to keep in mind when you’re looking at the Friday Mosque (aren’t they all) standing a few metres from the ancient Roman Hippodrome which was unearthed under a main street in the 1960s. There is even a bit of the hippodrome in the towns H&M, which is a little incongruous.

Back to the museum – the first room is mainly neolithic and chalcolithic, from the period when the Thracians who had turned up from further east mixed with local Slavic tribes, who had migrated south. The Thracians were known for their horsemanship and love of wine (as an aside, the Bulgarian wine is excellent and I regret not being able to bring back a bottle). The real treasure of the museum is found in the third room. In the 1930s three brothers were digging their farmland and uncovered an almost unimaginable hoard, perfectly preserved. Called the Panagyurishte Treasure, it consists of a table set of gold rhytons (drinking cups) and wine jugs, and one gold dish, originally made in Lapseki in Asia Minor at the turn of the 4th-3rd centuries BC and used by a Thracian king. The vessels are in the shapes of stags, sheep and women’s heads; the dish has concentric circles of ‘Ethiopian heads’ covering its base. They are breath-taking – clear, unblemished, bright yellow gold that looks as if it can’t possibly be real.

The other interesting object (really there are many more, but this one also has a good story behind it) is a helmet mask from the 1st century AD., which looks exactly like a human head made in silver and iron. It was discovered in the 1905 excavation of Kamenitsa Square in Plovdiv, and then, somehow, stolen in an armed robbery from the museum in 1995. It was finally relocated and returned to the museum in 2015 and despite its adventures remains well preserved, with an uncanny stare from its narrowed black eye slits.

Afterwards I walk back up to Nebet Tepe, one of Plovdiv’s seven hills – apparently there are technically only six hills, but perhaps because of the links to Byzantium they’ve decided to claim seven.* I spend a couple of hours up there now that the clouds have cleared, looking out over the city and to the distant mountains. There is a marked divide in Plovdiv between the red rooves and winding steep streets of the Old Town and Kapana, and the concrete breezeblock Khrushchevka-style tower blocks covering the rest of the city. But beyond that the mountains are still blue and misty and beautiful, their blanket of trees making them seem somehow like huge mossy stones.

*It transpires that there were once seven hills, until Markovo hill was destroyed in the early 20th century

Monday 15 July

Monday 15 July

As Plovdiv is relatively small and I had a good wander around the centre yesterday I decided to spend my second day visiting Bachkovo monastery and the fortress at Asenovgrad, both to the south of Plovdiv. A small local bus – essentially a minibus or a Russian marshrutka – runs from Plovdiv out through nearby towns and villages. I am the only one to get off at the monastery just south of Asenovgrad, after a journey of about 40 minutes into the hills.

The monastery is set against the Rhodope mountains, blue and tree covered. The visual tranquillity is broken a little when I visit by scaffolding and intermittent but extremely loud chainsawing which resounds through the monastery. Not something with the 11th century founder, Prince Gregory Pakourianos, could have foreseen as a pressing concern. The prince was a Byzantine commander and statesman from a Georgian family, and established the monastery as a centre of Georgian Orthodoxy in 1083. Later it was taken over by Bulgarian Orthodox monks, was looted during the Ottoman takeover of the country in the 15th century, and then restored in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is still in use – I walk past a couple of monks deep in conversation. There are several churches within the monastery compound, and all have a recognisably Byzantine style; like the Chora Church in Istanbul some are built of red-pink brick with think creamy mortar, and have several domes and cupolas. All the present churches date from the 17th century reconstruction of the monastery, apart from the medieval ossuary which stands a little way up the hill from the main complex.

There are murals inside and outside the buildings, with one on the outer wall of the refectory depicting the monastery’s founding and a schematic map of the complex. Inside, the refectory walls are decorated with extensive murals from floor to ceiling. I paid six leva to get in and watched the volunteer at the door write me out a receipt by hand and solemnly tear off and hand me the carbon copy. Things must move slowly in the mountains. It is hard to describe the hundreds of figures and biblical episodes painted on the refectory walls. The ceiling has a genealogy of Christ (like in the Chora Church but much larger and less striking), and at the entrance of the hall is a scene from the last judgement, lest the diners forget their maker.

I catch another of the intermittent buses back towards Asenovgrad to see the fortress – it is south of the town, so I retrace the road through the town for about 15 minutes. It is pretty – some concrete but not as much as in Plovdiv, and the mountains looming either side remind me of Switzerland. The road up to the fortress feels long but not that steep, since it winds around the hillside. When I reach the fortress I realise how high it is – I can see far across the valley and in the distance Asenovgrad spread out beneath me. Not much remains of the 9th century fortress, first founded by the Thracians and later renovated by Tsar Ivan Asen II in 1231, a Bulgarian ruler. It was taken by the Byzantines after Asen’s death and finally destroyed by the Ottomans during their rule of Bulgaria. The 12th or 13th century church is still standing and apparently in regular use. It is pink-red brick like the monastery churches and still has some 14th century murals inside. Like the fortress ruins, it perches on an outcrop of rock high above the valley – it would have been a formidable defensive position.

Asenovgrad station is the kind of tiny provincial station that doesn’t really exist in England any more, and this being the former Eastern bloc there is of course a station officer to sell me a ticket back to Plovdiv. It makes for a picturesque train journey, back past the hills with the low sun streaming in.

Tuesday 16 July

I spend the morning Plovdiv, getting lost in Kapana, since there are frequent trains and Sofia is less than three hours away. The journey is an uneventful stopping service – some of the stops are barely stations, just railway line, platform and derelict station house. People do get on and off so it is clearly still used and useful. Happily I have a window, as to my left the mountains accompany me all the way to Sofia.

Sofia – Wednesday 17 July

Sofia – Wednesday 17 July

A statue of Sofia stands high above the Serdika metro station and the Roman ruins in the city centre. The Roman city was known as Serdica, but as with Plovdiv there had already been a Thracian settlement there for centuries. On the opposite side of the long plaza is the Party House, formerly home to the Bulgarian Communist Party HQ and now just another government building.

My new interest in all things Thracian takes me into the Archaeological museum. The Thracians epitomise the area’s history – mixing tribes, cultures, borrowing from the Greeks and Romans (via Byzantium) but keeping a recognisable and distinct identity. Their precious objects were often variations of Hellenistic styles, but they also had their own particular styles – pectoral ornaments in gold (usually) and silver harness decorations for their beloved horses. There is gold everywhere, often very pure, as at some point rich gold seams where discovered in the north of Bulgaria ensuring they had a ready supply. Artefacts that caught my eye in the museum: a laurel wreath of beaten gold leaf, and a 23-carat diadem crown consisting of a golden cord with alternating lions and lioness walking above it, rings and toques. On one ring is an inscription in Greek letters in the Thracian language, which is one of the few surviving examples of Thracian since they didn’t have their own script. They must have been satisfied borrowing a script in the same way as they borrowed customs and ideas that suited them. The museum itself is housed in a former mosque, and stuffed full of marble, Cyrillic gospels and pottery: it’s yet another blend of Balkan, Byzantine and Ottoman.

Afterwards I walk over to the cathedral of Alexandra Nevsky, the most recognisable church in Sofia and probably the whole of Bulgaria. It sits in the middle of a square, gold-domed and green tinged, piled up like an ice cream sundae. It is relatively new – late 19th century – and inside is dark and heavily gilded, in contrast to the airy brightness of Istanbul’s mosques and older Orthodox churches. More interesting is the crypt which houses the National Art Gallery’s icon collection. They have an excellent collection of icons mostly from the 13th to the 19th century; I tend to prefer the earlier ones, which are simpler and more (icono)graphic. Across the road in the north-west corner of the square is the church of Sveta Sofia, at least 500 years older than the cathedral and a traditional Byzantine reddish colour, which gave the city its name.

Later in the afternoon I walk down boulevard Vitosha all the way to the National Palace of Culture and beyond it into the South Park, in sight of the Vitosha mountains which bookend the city. I’ve managed to see most of what I want to see in Sofia, and decide to go out to the Rila monastery the next day. Quiet and slow Sofia is very different to Istanbul, where I felt I had barely scratched the surface.

Thursday 18 July

Thursday 18 July

There is no easy public transport out to the mountains where Rila is, but fortunately there is a minivan running from the hostel. The monastery is about 120 km south of Sofia, on the slopes of the Rila mountain (Rila means ‘fresh spring’, and the mountain has the most sources of fresh water in Bulgaria); to get there we drive over the same gently rolling plain I crossed on my way from Plovdiv two days before. After two hours of bumpy road we get out to see the cave where the founder, St Ivan, lived as a hermit for seven years. If you climb up through a narrow tunnel in the cave then all your sins are forgiven. There’s also a spring of fresh, cool mountain water which was in the middle of being blessed by a chanting priest.

The monastery itself is very pretty, especially against the backdrop of the tree-covered mountains. The sky is criss-crossed with the blue and white feathers of swallows, as everywhere I’ve been in Bulgaria. The archways of the main church and the many-storied galleries of the courtyard are striped red and white, and the exteriors are covered in frescoes, including a series of almost comic-strip-like depictions of demons being brought before angels and looking perturbed.

Belgrade – Friday 19 July

Belgrade – Friday 19 July

My next destination is Herceg Novi on the coast of Montenegro, after which I’ll go cross over to Bosnia and Herzegovina and stop Sarajevo. As there’s no direct train or bus from Sofia I’m going via Belgrade, which gives me another bonus stop on my trip. The Belgrade bus station is predictably confusing and I leave the station by walking past an old abandoned railway station with weeds growing over the rusting rails and a deserted, derelict waiting room.

In a way I can’t pin down Belgrade has more of a sense of activity and movement than Sofia (which felt less like a capital city and more like a provincial town) – the streets are crowded and there’s construction work all along the river. The fortress is high on a hill in Old Belgrade, overlooking the river, the woods to the north and the streets of the old town. It is free to enter and the perfect place to spend a couple of peaceful hours walking about the gardens and grounds. There are signs of all its previous occupants – Serbs, Turks, Austrians. Sokollu Mehmed Pasha, a Serb who rose high in the Ottoman state, built one of the drinking fountains; Damad Ali Pasha, a Grand Vizier, has a mausoleum in the Upper Town. There’s the Stambol Gate and a gate/tower built by the Serbian despot Stefan Lazarević in the 15th century; there are memorials to the Ottoman siege of 1456 and to those who fought in WWII. In the soldiers’ chapel, if you look closely, you can see the chandeliers are made of forged sabres and rifle butts, hung with hundreds of bullets. The chapel is a recent and strangely peaceful memorial to the millions who died in and around the fortress, not to mention the citizens of Belgrade who have come under occupation every couple of centuries.

I’ve left myself an hour before my bus, which was a very good idea as it turns out that in addition to the bus ticket you have to buy a separate platform ticket from a dedicated desk, which seems absurd.

I wake up at 7.30am as the bus emerges from the mist on a winding road mountain road. Montenegro is of course very mountainous, and though I could already see Herceg Novi it took a couple of hours for the bus to get there, driving on a narrow and treacherous-seeming road between the mountains and the shore.

Herceg Novi – Saturday 20 and Sunday 21 July

Herceg Novi – Saturday 20 and Sunday 21 July

My friend Sara (who I originally met in Brussels when we were both on our years abroad) meets me at the bus station and takes me back to her grandmother’s house where I’ll be staying. I don’t speak Serbian and can only guess words and phrases that sound like Russian but Sara’s grandmother knows enough English from her Canadian grandchildren that we can get by.

Herceg Novi might look like an Adriatic seaside resort, but it has a very interesting history. Stari grad (the old town) is about a thousand years old, though most of the buildings now are much more recent than that. The Spanish, Venetians, Ottomans and Serbs have all occupied it at one time or another, leaving behind fortresses and a mix of architecture. It sits in the Bay of Kotor, which protects it from the drama of the open sea and makes it very attractive to visitors who come mainly from Russia and Serbia. For some reason Montenegro uses the euro, despite not being in the EU – from what I gather it started as a temporary measure and then was so convenient they never changed back.

After a busy couple of weeks I enjoy just walking about the town and swimming in the warm sea. The water here is preternaturally blue and clear, and aside from the wake of an occasional massive cruise liner is usually undisturbed. The town is built on a hill and I must have climbed up and down hundreds of steps in the few days I was there, up and down through the narrow medieval streets with their painted houses and balconies.

Monday 22 and Tuesday 23 July

Monday 22 and Tuesday 23 July

The weather breaks today, after a sunny early morning perfect for swimming, with thunder and pelting rain. When it clears up around midday we head to the Spanelsko fortress, up on the hill above the old town reached by yet more stairs. The storm is still in the air, and with the green of the forested hills and loud insects it feels more tropical than Balkan. The fortress is not really Spanish at all, or at least was only Spanish for about 30 years before being captured and rebuilt by the Ottomans. In WWII it was used as a fortress or depot and inside there are rusted curved rooves of corrugated iron covering concrete tunnels, which I presume date from that time. The place is very neglected, overgrown with weeds and with a tree growing in the middle of one ruined room. The tower walls are covered in graffiti – ‘Kosovo is Serbia’ being a memorable example.

The next day I visit the two other surviving fortresses of Herceg Novi (the name itself means ‘new castle’). Before that me and Sara visit the Savina monastery, walking past memorials to WWII freedom fighters against fascism. It is white with red-tiled roof and cupola, and a tall tower on the church in the centre of the courtyard. To the east you can see a field with serried rows of vines and a sprinkling of olive trees. Inside the church is cool and white, while above my head the inside of the dome is painted sky-blue. The paint is flaking off quite baldly in places to reveal the white underneath in cloudlike patches. The rest of the church is rich and dark with carpets and gilding, a heavy chandelier with ostrich eggs hanging low over the nave and an iconostasis with some unusual gold metal suns and cut-out angels at the top, just below a crucifix and skull and crossbones.

The walk down from the monastery to the Ottoman fortress is steep but short; Kanli Kula is still quite high up, with a wide view over the sea and town. It now has an amphitheatre in the centre and is used for theatre and film screenings. There is an old dungeon cell you can go into which still has visible marks on the walls made by prisoners counting off the days. Even in the heat it’s dank and mouldering, and I imagine the unfortunates kept here would have either burnt under the harsh sun or frozen in the winter. The final fortress, Fortemare, was built by the Venetians and is the closest to the sea (there used to be another Italian fortress which fell into the sea some time in the 1960s).

That evening Sara’s grandmother makes us a cheese pita, which is a kind of incredibly delicious pastry pie, made of layers of kajmak (a hard to describe creamy dairy product a bit like clotted cream), cheese and pastry. Afterwards we watch the sunset across the sea, and I pack for the last stage of my trip.

By Bus through Bosnia & Herzegovina – Wednesday 24 July

By Bus through Bosnia & Herzegovina – Wednesday 24 July

I have another day in the bus ahead of me – I leave Herceg Novi at 8.45am, crossing over the border into Bosnia and Herzegovina a couple of hours later and finally arriving in Sarajevo at 4pm.

The road takes us up into the mountains and then down into a valley, past occasional villages and small towns, with mosques and minarets and sometimes a church. As we enter Mostar we pass a cemetery full of crosses and then another filled with gravestones like miniature obelisks. There are many signs of the civil war, in the still visible bullet holes, graffiti referencing Srebrenica, and in a gigantic cross which stands high on a hill above (which I find out later is considered by many of the divided city’s Muslim residents to be a provocation by the Croatians, who had also destroyed the historic Ottoman bridge during the siege).After Mostar the scenery changes and the bus goes in and out of tunnels in the wooded hillsides above a wide green river which fills the bottom of the valley completely. When we get into Sarajevo kanton the valleys flatten a bit and haystacks and alpine-looking houses with wide rooves appear.

I finally arrive in Sarajevo in the late afternoon, and after exchanging my last euros for some misleadingly named convertible marks I make my way from the bus station, past the American embassy and into the centre. As I’m only here for a short time I want to fit in as much as possible, and so follow the hostel manager’s recommendation to take the cable car up the mountain to the site of the 1984 Olympic bobsleigh track. I get a brilliant view of Sarajevo as the sun sets over the surrounding mountains with an orange warmth (though it is quite high up and definitely a few degrees colder). The bobsleigh track itself is overgrown and covered in graffiti, and as I approach a stray dog hurries away into the undergrowth. You can walk down the whole track, but it is a little bleak seeming and as the light is failing I don’t feel inclined to go too far into the woods.

Sarajevo – Thursday 25 July

Sarajevo – Thursday 25 July

My first stop in the morning is an obvious one – the infamous bridge where Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, which while not exactly underwhelming seems such an incongruous place for an event that kicked off a European-wide war. It’s a beautiful morning, the water in the low river glassy-clear and reflecting the early sun. I walk up along the river, past the yellow sweet-striped town hall and then turn left onto Telali Street and along to Sebilj fountain in the marketplace, which is already getting busy with locals and tourists. Then I walk down the main market street which goes past many of the centre’s important buildings and monuments. The split between the Asian side and European side is dramatically visible along Ferhadija street – walking from east to west the low two storey houses suddenly become baroque, pastel-painted tall buildings like you’d find in Prague or Vienna. This is even marked by a sign on the wall declaring Sarajevo to be the ‘meeting place of cultures’ and some lined paving which when I visit is half-way complete. Before I reach this point I stop into the central mosque, Ghazi Husner-Bey mosque, which is a peaceful place for worshippers and tourists alike off the hectic street.

My next stop is the Old Jewish Synagogue, less than five minutes down the road from the mosque, which houses the Jewish museum. I had been vaguely aware of the Sarajevo Jewish community, but from the museum I discover just how long it had existed in Sarajevo – from the middle ages, following the expulsion of the Sephardic Jews from Spain and Portugal, until WWII, when under fascist occupation by Italy many were deported to concentration camps and executed. The Old Synagogue is now a museum to the pre-war Jewish way of life in Sarajevo, and to the experiences of the Holocaust, with a display of anti-Jewish, anti-communist and fascist propaganda posters, information about the Jewish fighters in the Bosnian resistance, and lists of the names of the Sarajevo and Bosnian Jews killed in WWII and the Righteous Among the Nations who helped others to escape. There are many objects from the 19th and 20th centuries, and most interestingly a copy of the Sarajevo Haggadah, which was hidden under a church porch during WWII and so survived the looting and destruction.

There are several museums focusing on the 1990s conflict, but I decide to visit Galerija 11/07/95, beside the Sacred Heart cathedral, which focuses on the Srebrenica massacre. The first room contains portraits of the Bosniaks, mostly men and boys, who were killed in Srebrenica on and after 11th August 1995. The audioguide is essential to get the most from this museum, as it has testimony from witnesses and survivors as well as giving a clear account of the events. In the next room are photographs from a Bosnian photographer who has spent the last 20 years visiting refugee camps, where many displaced Bosnian Muslims still live, and the sites of mass graves. Some photographs document the frozen lives of the survivors and victims’ families, while others are graphic shots of bones and skulls being unearthed in piles. It is an incredibly powerful exhibition, and it is jarring to leave the dark building and step back into the bright July sun.

I pay a short visit to Despić House, which is interesting because it’s almost like an Ottoman house inside a ‘European’ exterior. It began as a one-room Ottoman house, owned by the Despić family who then bought the house next door, and eventually joined them together with an upper storey and encased them both with a European façade. The two downstairs rooms have been kept like early 19th century Ottoman rooms, complete with carpets, divans/sofas and Ottoman plate. Upstairs there are several smaller rooms styled more like those of a bourgeois central European household of the late 19th century. After that, conscious of my 6pm bus, I make a quick stop in a café down a side-street for some baklava (apparently Sarajevo has the best baklava in the Balkans) and coffee, and then head to my bus.

My stay in Sarajevo was brief, but left me with a real urge to return – the same with Istanbul and Belgrade. My trip has managed to include cities, the sea, the mountains and even a (small) cave, and the contrast between the places I’ve visited has helped me to appreciate each one in its own way. When I originally applied for the award I had no idea how much I would love Istanbul, and I am looking forward to going back and exploring more of Turkey when I can. I would like to thank the Roger Short Memorial Trust for giving me this opportunity, and in particular Victoria Short for her hospitality and advice while I was in Istanbul.

Francesca Sollohub, August 2019

Tips for travellers

Travelling by bus: there is a good bus network in Turkey and the Balkans, with more options than the railway. I would recommend using buses but do try where possible to buy your ticket at the station in advance – there are various websites that sell online tickets but you often need to print them out, and the drivers are not always sure what to do with them. If there are border crossings involved then expect delays of an hour plus and leave yourself plenty of time for any connections. Take enough water and food in case there are long delays, as the bus won’t stop that often. Hand sanitizer and tissues are also useful.

Money: you will need to carry cash and can’t rely on being able to pay by card or find an ATM, especially out of the cities and on local transport. Since I was visiting several countries I used a Caxton FX currency card and app, which I’ve had for a few years, to minimise withdrawal fees and pay in local currency – there are plenty of other options available online.

Istanbul transport – if you’re staying for a few days I would recommend getting an Istanbul Kart which works like an Oyster card and can be used on the tram, metro and the ferries. Taking ferries is a great way to get between different parts of the city and have a good view.

Find out more about the range of travel grants and scholarships available to assist Univ students on our Travel Grants page or read further travel reports.

Published: 2 December 2019

Explore Univ on social media