A Bursar’s wartime in-tray

Just recently in the archives I have been cataloguing some miscellaneous papers of A. B. Poynton concerning his work as Bursar. Arthur Blackbourne Poynton was one of the most important Fellows of Univ during the early 20th century: he was Classics Fellow from 1894–1935 and Master from 1935–7, and from 1900 he was also the College Bursar. In fact, he was the last Bursar of Univ to handle both estate and domestic matters until a separate post of Domestic Bursar was created in 1926 – and even then Poynton remained Estates Bursar until 1935. Poynton preserved many of his papers, which shed new light on many aspects of College life during the early 20th century.

Several of these newly catalogued papers relate to Poynton’s activities during the First World War, and, as Remembrance Sunday draws near, it seems appropriate to look at some of this material for a Bursar’s perspective on this terrible time. They are often rather mundane documents, but they shed new and unexpected light on the effects of the war and its aftermath on the College and its members.

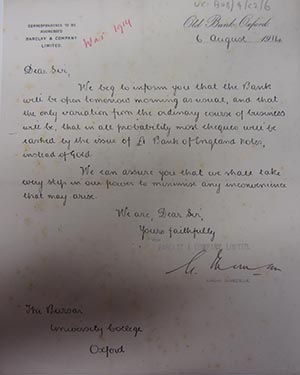

The first item on show (see above: ref. UC:BU8/4/C2/6) is a letter from the manager of the College’s bank, dated 6 August 1914, assuring its clients that the bank would be open on the following day as usual.

In the uncertain times immediately after the declaration of war, there would certainly have been concerns about runs on banks, and so this reassuring letter would have been appreciated.

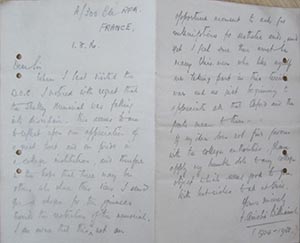

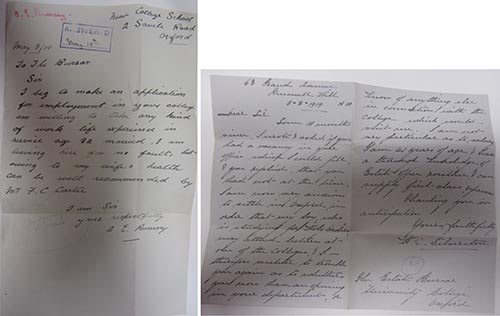

The collection includes some letters to Poynton from Old Members. This one (ref. UC:BU8/4/C2/1) was written on 1 August 1916 by Frank Ainslie Williams (matr. 1904), when he was serving in France. Williams was by now a Major in the 5th London Rifle Brigade, and he would later receive the Croix de Guerre. Even when on active service, however, Williams had not forgotten something which annoyed him when he last visited Univ, namely that the Shelley Memorial “was falling into disrepair”. So he asked whether an appeal could be set up for the Memorial, and even sent a cheque for 10 guineas as a starting point.

Williams goes on: “This is not an opportune moment to ask for subscriptions for aesthetic ends, and yet I feel sure there must be many Univ men who like myself are taking part in this terrible war and are just beginning to appreciate all that Oxford and the poets mean to them.” He shows very clearly that, for Univ men serving on the front line, memories of their Oxford years were a genuine source of comfort.

One hopes that Poynton followed Williams’s request. In the light of his strictures on the Shelley Memorial, it is unsurprising that, on his death in 1961, Williams left £100 to the College towards the upkeep of its buildings.

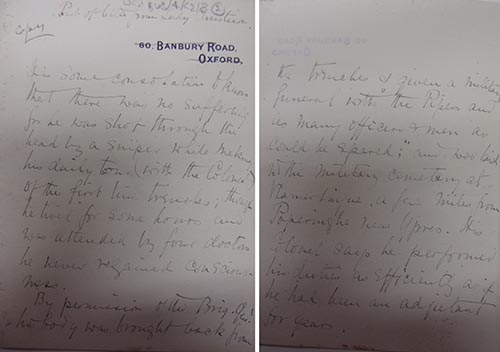

Sometimes Poynton heard from the friends or families of Old Members who had been killed in action. Below is a copy of a letter (Ref. UC:BU8/4/C2/8) from Florence, Lady Christison, from December 1915, about the death of her son Frederick (matr. 1913). In it she talks of how he was killed without suffering, after being shot in the head by a sniper when walking around the trenches. One would like to believe that Frederick Christison did indeed die as his mother had been told, but not infrequently officers writing to bereaved families took the gentler course of not revealing the whole truth if in fact their relative’s death had been a great deal more distressing.

Frederick’s older brother Philip had also come up to Univ. Fortunately, he survived the war, and later became a distinguished solder in his own right.

Many Fellows of Univ spent the war away from College. Some of them were on active service, but others performed various kinds of clerical war work. Poynton was one of the very few Fellows who saw out the war from the College. As the war ended, so the absent Fellows were trying to arrange their demobilisation, so that they could return to Oxford, and several of Poynton’s war papers are concerned with this.

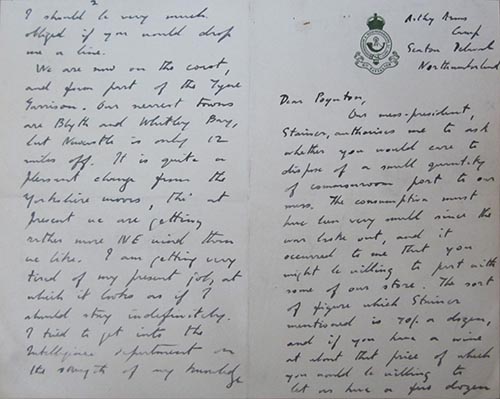

Below is a letter (Ref UC:BU8/4/C20) from the Ancient History Fellow George Hope Stevenson (F. 1906–49), written when he was stationed up in Northumberland. He spent part of the war working in Intelligence. The opening is somewhat surreal: Stevenson is writing because the President of his mess was wondering whether he could buy up some port from the Senior Common Room’s store. As Stevenson put it, “The consumption must have been very small since the war broke out.” On the other hand, as the letter goes on, so Stevenson’s frustrations start to reveal themselves; although he prefers the Northumberland coast to the Yorkshire moors, “at present we are getting rather more NE wind than we like” and “I am getting very tired of my present job, at which it looks as if I should stay indefinitely.”

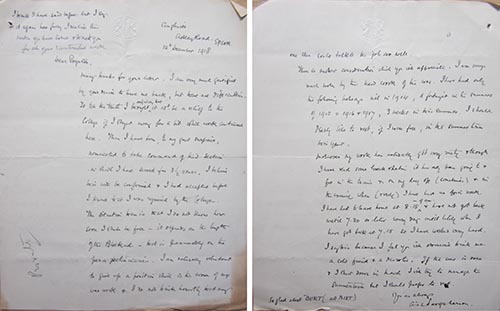

A letter of 12 December 1918 (below, Ref UC:BU8/4/C17) from the Philosophy Fellow, A. S. L. Farquharson (F 1899–1942), known to all as “Farky”, written at the end of the war, sheds interesting light on some of the other problems facing Fellows returning to teaching duties. Farky had spent the war working for the General Staff at the War Office, first in Military Operations and then, like Stevenson, in Intelligence. Farky was evidently more highly thought of than Stevenson, because, at the time of his letter to Poynton, he had just been invited to take command of his section (which he did: from 1919-21 he was Chief Postal Censor). In 1919 he would be made both a CBE and an officer of the Legion d’Honneur.

In thinking about his future, Farky touches on two important details. First of all, he has barely had any holidays during the war, and writes “I should dearly like to rest, if I were free, in the summer term this year.” He continues: “Moreover my work has naturally got very rusty & though I have read some Greek & Latin it has only been going to & fro in the trains & on my day off (sometimes) & in the evening when (rarely) I have had no office work.”

Farky will not have been alone among Oxford dons in feeling some apprehension that he has had no chance to keep in touch with his subject for so long, and now needs to relearn so much.

The Fellows writing to Poynton at the end of the war could feel assured that, once they were demobilised, they would have jobs to return to. One unexpected discovery among Poynton’s war papers sheds light on a group of men who were less lucky. These were demobbed ex-servicemen who had no jobs to return to, and who now desperately needed to find work.

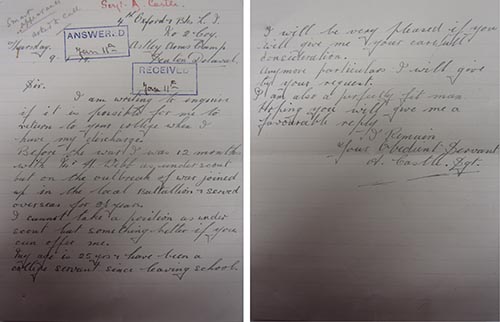

Poynton’s papers include three bundles of correspondence sent to him from demobbed soldiers asking if there were any vacancies for servants’ posts within the College. Some of those writing in had worked for the College before, and were indeed able to return to employment here. Below is a letter (ref. UC:BU8/4/C4/15) from Arthur Castle, who had briefly worked at the College before joining up. Castle evidently made a good impression, for Poynton noted on his letter “Smart appearance. Asked to call.” He was taken back into College employment, and stayed at Univ for the rest of his working life, eventually becoming a much respected SCR Scout.

Not every applicant was so lucky, as these two letters (ref. UC:BU8/4/C4/21) show. On one of them, Poynton wrote “no vacancy at present”, and on the other – bluntly – “no”.

The two letters provide vivid evidence of the problems faced by so many ex-servicemen after the war in finding employment.

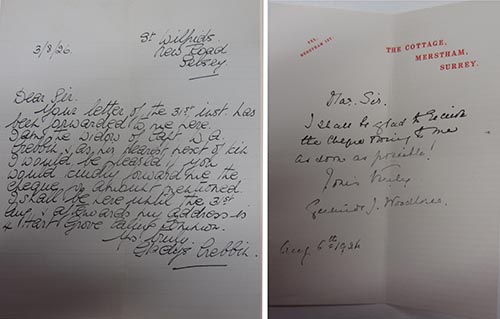

Long after postwar life at Univ returned to normal, there were some pieces of Bursarial business arising from the war which took longer to settle. One of the more poignant was the question of caution money for students killed in the war. Until quite recently, every fresher on coming up to Oxford would pay a deposit called “caution money” which they could claim back or not when they left.

In 1926, it seems, Poynton decided that it was time to settle the affairs of those members of the College who had been killed in the war, and he therefore wrote to their families asking if they wanted their money back. A group of their replies survive. Most letters are reasonably businesslike, like these two below (ref. UC:BU8/4/C2/25), from Gertrude Woodhouse, the widowed mother of Reginald (matr. 1909; d. 1916) and Gladys, the widow of William Crebbin (matr. 1913; d. 1918), in which, just like every correspondent, they express their wish to receive the caution money, albeit very bluntly, in Gertrude Woodhouse’s case. One suspects that widows, in particular, would have been glad of this little financial windfall.

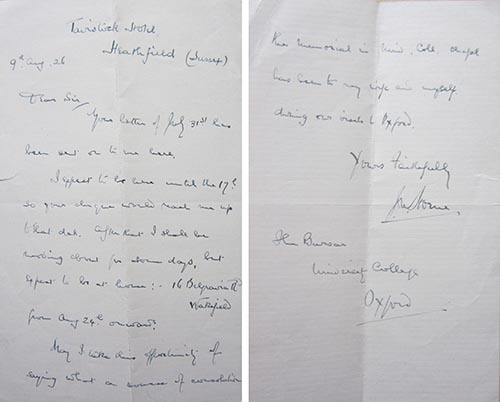

Some writers, however, make the time to say a little more. One such (below, ref. UC:BU8/4/C2/25) is John Horne whose son Leonard had come up in 1912, and who been killed in 1918. Horne had had a chance to visit the College’s War Memorial, and it clearly meant much to him, for he wrote: “May I take this opportunity of saying what a source of consolation the memorial in Univ, Coll. Chapel has been to my wife and myself during our visits to Oxford.”

There is no one left alive now who knew any of the young men on our First World War memorial, and it is good to go back to a time when those names still rekindled memories of once living people.

Published: 2 November 2022

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.