Univ: plague & war part 2

Part 2: Civil War

As seen in my last article (Part 1: plague and pandemic), University College and its members escaped previous pandemics relatively lightly, both in terms of loss of life or damage to finances. However, when we turn to the College in times of war, the story is very different. In this article, I will consider the two greatest civil wars in English history, the Wars of the Roses, and the English Civil War.

The Battle of Towton, as imagined in 1922 by Richard Caton Woodville

The Wars of the Roses

The later fifteenth century is overshadowed by the struggle between the houses of York and Lancaster, known as “The Wars of the Roses”. This war is generally reckoned to have lasted from 1455 until 1485, ending with the victory of Henry VII at Bosworth. However, the actual periods of fighting were quite short-lived, and there were long periods of peace in between. Nevertheless, those periods of fighting were intense: the battle of Towton, of 29 March 1461, was almost certainly the bloodiest battle ever fought on British soil.

None of the campaigns of the Wars of the Roses went near Oxford, and so the University was spared immediate danger. Nevertheless, the war touched Oxford in other ways. As with the Black Death, there are no first-hand testimonies from Univ men about the Wars of the Roses, but one document in the archives reveals just how difficult times could be.

That document is the College’s account roll for the financial year running from Pentecost (1 June) 1460 to Pentecost (24 May) 1461. It can be read in the edition of our account rolls prepared by David Cox and myself and published back in 1999.

At first glance, all seems normal: rents from College properties amount to £85 18s 4½d, which is typical of normal years. But something amiss is going on. Fellows in medieval times would receive an annual stipend, and in the 1450s, that stipend is usually £1 6s 8d. In 1460/1 the Master and Fellows received stipends of a mere 6s 8d each.

That account roll needs further questioning. In fact the section headed “rents” (Redditus in Latin) actually records rents which the College hoped to receive in a given year. Accounts of this time also include sections called “arrears” (Arreragia) and “allowances” (Allocaciones). The arrears records rents which were outstanding at the start of a financial year, and the allowances rents outstanding at its end. In order, therefore, to calculate Univ’s real income in a given year, one has to add together the arrears and rents, and deduct the allowances from it. I am the first to agree that this is counter-intuitive to a modern reader; but a Bursar could thus show an auditor what rents he had or had not been able to collect.

When one runs the accounts of the 1450s through this process, then Univ emerges as doing well, with an actual income closely matching its expected income. But in 1460/1, the College’s real income collapsed to £38 4s 4½d – cut by more than half from previous years. The greatest loss was in income from estates outside Oxford. The rental for these properties was set at £48 6d, but in 1460/1 the College actually received £14 9s 7d.

We can guess easily enough what happened. The only way for a medieval Bursar to collect rent was to ride out and get it. Remember here that Towton was fought in March 1461. This was the terrible climax of a succession of bloody battles fought all though 1460 and 1461, including at Northampton, Wakefield and St. Albans.

That year’s Bursar, John Hulle, would have realised that it was folly to try to collect any rents outside the city. He and the College evidently preferred to stay safe in Oxford, even at the cost of a collapse in their own income.

The College’s caution was rewarded as the new king, Edward IV, brought some stability to the country. In the financial year ending in Pentecost 1462 Univ’s real income shot up to £98 1s 6¾, of which £65 3s 11d came from the College’s properties outside Oxford. The new Bursar had clearly considered it safe enough to leave Oxford, and had persuaded our tenants to pay him much of their arrears from the previous year.

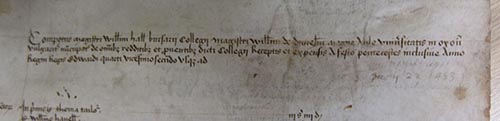

Political instability affected the medieval College one last time. The Bursar for 1482/3, William Hall, was writing up his accounts at some point in the summer of 1483. The financial year should have ended at Pentecost 1483 (18 May), which fell during the short reign of Edward V, by now deposed by his uncle. Hall dated his roll, like his predecessors, by regnal year, and so he began by dating his roll “from the feast of Pentecost in the 22nd year of the reign of King Edward the Fourth until….” But what should he write next – the first year of Edward V, or the first year of Richard III? So, as you can see from the photo below, he prudently left it blank.

Interestingly, in the following year’s account, the then Bursar, Christopher Forster, ducked the whole problem by dating his roll by the Christian era.

Sir Simon Bennett (1584-1633)

The English Civil War

The 1630s had been a good decade for Univ. Our Master, Thomas Walker, had married a niece of the Archbishop of Canterbury, William Laud, and good progress had been made on the construction of a grand new quadrangle, which was now more than half finished, mainly thanks to a major benefaction from an Old Member, Sir Simon Bennet. By 1640 the College was in negotiations with the best glass painter in Oxford, the Dutchman Abraham van Linge, about his creating windows for the new Chapel. The 1640s and 1650s, however, would be perhaps the darkest time in our history.

In 1640, as Parliament met for the first time in eleven years, so the country found itself divided between supporters of Charles I and Parliament. Glimpses of how the political crisis touched Univ can be found in a rather unexpected source, namely the College’s Buttery Books, which record the daily expenditure of its members. They thus also record who is actually in College at any given date. In a previous Univ Treasure, which you can find here, I discuss those Buttery Books in more detail. You will find there evidence for how the College dispersed as war broke out – but also some of the amusing, and sometimes disturbing, comments added by the Buttery Clerk.

Unlike with the Wars of the Roses, Oxford came under threat almost at once. In September and October 1642, Oxford was occupied, first by some Royalist soldiers, and then by some Parliamentarian ones. As can be seen in the Buttery Books, on the week beginning 2 September, almost everyone who could got out of Univ, and within a fortnight the only people left in College were four Fellows, two MA’s, two BA’s, and four undergraduates.

The College swiftly filled up again in other ways, for in late October Charles I himself came to Oxford with his court. The King lived in Christ Church and the courtiers found accommodation where they could in the Colleges. Several Old Members took up residence in Univ, including Sir George Radcliffe, whose undergraduate memories of plague at Oxford were quoted in my last piece. Some women of the court also lived in College – the first women to do so.

Of course the College’s building programme ground to a halt, so that the College was left an architectural mess, with parts of the old and new quadrangles interlocking with each other. Van Linge had completed all his windows for the Chapel, apart from a great east window, which would never be created. His remaining windows were placed in storage.

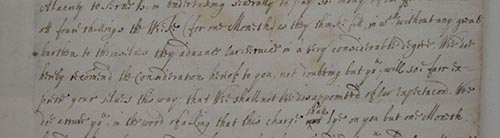

Oxford was thus right at the centre of the war. The Colleges and their heads were overwhelmingly Royalist, and so Charles could rely on their loyalty. That loyalty, however, and the presence of the King, proved costly. In January 1643, along with other Colleges, Univ gave its plate to the King, and it was inevitably melted for coin. Thus we have no silver in the College which dates from before the Civil War. The King had other ways of raising money: in July 1643, he wrote to the College inviting them to support as many of his soldiers as they could for a month. He coolly noted that he was “not doubting but you will so farr expresse your selves this way that Wee shall not be disappointed of Our expectation”, and the Master and Fellows will have known what to do.

View the full letter here (new window)

There were other perils: in June 1643, all scholars in Oxford aged between 16 and 60 were asked to spend one day a week building fortifications. This could be dangerous work: one of our undergraduates, Richard Tennant, drowned in the Cherwell, perhaps working there. Meanwhile, next to no new undergraduates came up to the College. There are just two new arrivals recorded in 1643, four in 1644, and none at all in 1645 and 1646.

As the war continued, once again the College’s income suffered, as it became ever harder to visit its estates. In 1643/4, the College should have received £470 in rent, but the Bursar of the time, William Richardson, noted that some £220 was not paid. Some tenants even tried to wriggle out of their responsibilities: In February 1648, the parishioners of Arncliffe, claimed that the College had no right to demand tithes from them – for all that they had been paying them without demur for almost two centuries. Some College properties were damaged during the war. A house in Woodstock was reported in March 1646 as being “much decayed by reason of these unruly times”.

Unsurprisingly, just as in 1460/1, so those living in the College found their incomes fall. The College annual expenditure declined from an average of £450 in the 1630s to a mere £275 in 1646/7.

One of the unhappier aspects of the Civil War was that members of Univ ended up fighting on both sides. On the whole, it seems to have been the older Old Members, up before Walker’s Mastership, who supported Parliament, while Univ men of Walker’s generation were mostly Royalist. One Fellow even drew up a list of 33 Old Members whom he knew were fighting for the King, five of whom died in battle or of illness. Two of Univ’s Parliamentarians, Henry Marten and William Say, were even among those who signed Charles I’s death warrant.

After Charles I’s eventual defeat, Oxford surrendered in 1646. Thomas Fairfax, Parliament’s commander, was merciful, and lert the city untouched. However, in May 1647 the Parliamentarians instituted a group of Visitors to inspect Oxford, and seek out those who might oppose the new regime. When the visitation of Oxford was held in the spring of 1648, Thomas Walker and over half the Fellows were expelled for refusing to swear allegiance to the authority of Parliament, and a new Master with no previous links to the College, Joshua Hoyle, was installed.

During the 1640s, the College had endured war, financial troubles, and a purge, but things hardly improved in the 1650s. Unfortunately, Hoyle proved an ineffectual Master, incapable of putting the College’s finances to rights.

One of the greatest financial problems was caused by Sir Simon Bennet’s benefaction. As well as arranging to pay for a new quadrangle, Bennet had arranged that the estate he bequeathed to Univ., Handley Park in Northamptonshire, should endow new Fellowships and Scholarships. Unfortunately he didn’t specify how many Fellows and Scholars there should be. Bennet’s family felt that they should benefit from this bequest, and in late 1649 took the College to court. The court decreed that income from Handley Park should support eight Fellows and eight Scholars, half of whom had to be kinsmen to Sir Simon Bennet – although Bennet had made no stipulation for this in his will. Bennet’s family were too greedy: Handley Park never produced enough money to support so many people, and in February 1654, the Parliamentary Visitors had to decree that the Fellows on the Bennet foundation could not be paid for three and a half years.

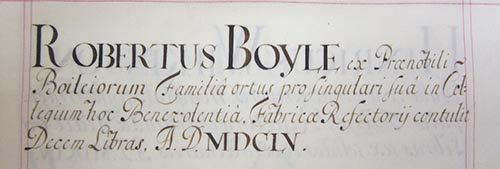

The College did complete one successful initiative during the 1650s, for in 1656/7 the Master and Fellows gave the Hall its splendid hammerbeam roof. It was not easy, though: most Old Members of the College refused to have anything to do with a Master and Fellowship they regarded as illegal intruders, and the College had to raise money from where it could. Thus an aristocratic natural philosopher renting a house next to Univ (now the site of the Shelley Memorial) was persuaded to give £10 towards the project. That is Robert Boyle’s only link with Univ.

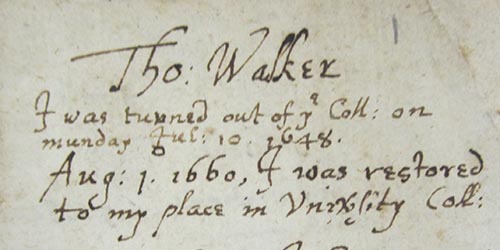

On the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, a fresh visitation of Oxford was held, and surviving Royalists, like Thomas Walker, were now reinstalled in their posts. Walker in one of his account books took private pleasure in recording the exact dates of his expulsion and return.

It must have been a hard moment for Walker to return to his College to find its finances in chaos, and its building project barely advanced in two decades. Walker himself was now in his late sixties, and only lived another five years. Yet Walker improved the College’s fortunes. The Chapel was at last finished, although it was not dedicated until after Walker’s death. Walker took the Bennet family back to court, and in 1662 had the judgement of 1649 overturned. Now Handley Park would support just four Fellows and four Scholars, and there would be no preference given to Bennet’s kinsmen (as it happened, William Laud had suggested this solution back in 1640, but who was going to listen to him then?). This prudent decision at last rendered the Bennet foundation practicable.

The College’s debts were still not completely settled by the time of Walker’s death in 1665, and it would take another eleven years to complete the Main Quad, but at least Univ was a great deal closer to the position it had been in 1640 than in many years – for all that it had taken a quarter of a century to get there once more.

In the next and final piece, I will write about how Univ survived the two World Wars of the 20th century. The College suffered greatly during both conflicts, not least in the tragic deaths of so many of its members. However in terms of the terrible mixture of actual danger, loss of life, and financial catastrophe, the English Civil War was perhaps the College’s darkest hour, and the one from which it took longest to recover.

Univ: plague & war – part 3 will be published in due course.

Robin Darwall-Smith, Archivist

Published: 14 April 2020

Explore Univ on social media