Fellow in focus: Joe Moshenska

My office in Univ is in 90 High Street, which means that my daily walks to lunch or my pigeonhole take me back and forth past the Shelley Memorial. I’ve become used to these frequent glimpses of the naked marble body of the great poet since I arrived at Univ in 2018, but my experience of them is always inflected by the fact that – as a plaque on the High Street side of the wall records – this is a spot that features several historical layers. Two and a half centuries before marble Shelley was plonked there, this was the site of the house where the great chemist and natural philosopher Robert Boyle performed his experiments with an air pump, exploring the possible existence of a vacuum, and what is now the easternmost slice of the Fellows’ Garden was Boyle’s long, thin back garden.

My office in Univ is in 90 High Street, which means that my daily walks to lunch or my pigeonhole take me back and forth past the Shelley Memorial. I’ve become used to these frequent glimpses of the naked marble body of the great poet since I arrived at Univ in 2018, but my experience of them is always inflected by the fact that – as a plaque on the High Street side of the wall records – this is a spot that features several historical layers. Two and a half centuries before marble Shelley was plonked there, this was the site of the house where the great chemist and natural philosopher Robert Boyle performed his experiments with an air pump, exploring the possible existence of a vacuum, and what is now the easternmost slice of the Fellows’ Garden was Boyle’s long, thin back garden.

I mention these accidents of historical convergence because I’ve always been interested in my work – which focuses on the period of Boyle’s lifetime and a little before, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – in the ways that histories tend to get piled atop one another, and the peculiar kind of access that literary works give to these histories, the traces that they leave, and human experiences of them.

I mention these accidents of historical convergence because I’ve always been interested in my work – which focuses on the period of Boyle’s lifetime and a little before, the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries – in the ways that histories tend to get piled atop one another, and the peculiar kind of access that literary works give to these histories, the traces that they leave, and human experiences of them.

It’s also fitting that Boyle and Shelley, a scientist and a poet, converge in this space since I’ve always been interested in moving between literature and other fields of culture and human endeavour. I tend in my work to return to two complicated and inexhaustible poets – Edmund Spenser and John Milton – but to move back and forth between the minute linguistic workings of their great poems, and the histories of religion, philosophy, science, and art, as well as critical and cultural theory. This was true of my first book, on the sense of touch in renaissance England, which included chapters on relics, statues, the early reception of Chinese medicine in England, and the philosophical history of tickling; it was true in a different way of the book that I published soon after moving to Univ, Iconoclasm as Child’s Play, which traced the practice of giving formerly holy things to children as toys during the Reformation, a project that took me not just back to Spenser, but through the long history of philosophies and theories of play. I maintain my love of Spenser even when not reading him through my role as President of the International Spenser Society, in which I founded a Zoom reading group during the pandemic where we choose – and discuss – a stanza from The Faerie Queene using a random number generator – email me if you’re interested in trying it!

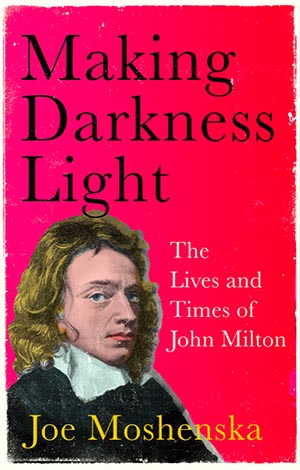

If I’m interested via my academic work in connecting literature to other areas of thought and practice, I’m equally keen to connect with wide and varied audiences. Two of my books – A Stain in the Blood, on the 1628 Mediterranean voyage of the polymath Kenelm Digby, and Making Darkness Light, an experimental biography of Milton – are aimed at a general readership. I firmly believe that, while it’s important to maintain the scholarly standards for which Oxford is renowned, it’s also crucial that we find ways to communicate the value of literature to the wider world if the subject is to survive and flourish. For similar reasons I’ve enjoyed sharing my ideas via the radio, frequently appearing on Radio 3 to discuss topics as varied as Caravaggio, the photographer Cindy Sherman, the human knee, and the history of the bedroom, and in 2017

If I’m interested via my academic work in connecting literature to other areas of thought and practice, I’m equally keen to connect with wide and varied audiences. Two of my books – A Stain in the Blood, on the 1628 Mediterranean voyage of the polymath Kenelm Digby, and Making Darkness Light, an experimental biography of Milton – are aimed at a general readership. I firmly believe that, while it’s important to maintain the scholarly standards for which Oxford is renowned, it’s also crucial that we find ways to communicate the value of literature to the wider world if the subject is to survive and flourish. For similar reasons I’ve enjoyed sharing my ideas via the radio, frequently appearing on Radio 3 to discuss topics as varied as Caravaggio, the photographer Cindy Sherman, the human knee, and the history of the bedroom, and in 2017

I presented a Radio 4 documentary on Milton for which I had the chance to visit Galileo’s villa outside Florence, where he and Milton probably met.

The great joy of teaching at Univ is that it gives me the chance to experiment with my teaching in the way that I enjoy experimenting in my research. Last term I ran a reading group with the second-year students on Rabelais’s Gargantua and Pantagruel where we met weekly, often over breakfast in hall, for a different kind of discussion. This term, I teamed up with a colleague from another college to take them for a walk around Oxford to sites where Boyle’s friends and contemporaries participated in the acceleration of the Scientific Revolution – a reminder that to study, teach and work in Univ is to be surrounded by histories, some as visible and startling as the Shelley Memorial, others that you need to know to look for.

Professor Joe Moshenska, Beaverbrook and Bouverie Tutorial Fellow in English and Professor of English Literature

This feature was adapted from one first published in Issue 15 of The Martlet; read the full magazine here or explore our back catalogue of Martlets below:

Published: 18 July 2023