From Rock and Roll to Royalty

Nigel Tully MBE (1961, Physics) is co-founder, bandleader and singer/guitarist with The Dark Blues, one of Britain’s most popular party bands. Their career highlights include Royal Family private parties at Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, and working with Phil Collins – who played alongside the band at HRH Prince Charles’ 40th birthday and then asked them to play for his wife’s party in Geneva on Millennium Night. Nigel formed the band (originally known as The Fourbeats) while a student at Univ in the 1960s. He has made over 5,000 appearances in over 50 years as the leader of the band. They have played at, among other venues, the Savoy Hotel, Claridge’s, Cliveden, Spencer House, the Natural History Museum, Blenheim Palace and Hampton Court Palace. Nigel is also Chair of the NYJO (the National Youth Jazz Orchestra of the UK), Pastmaster of The Worshipful Company of Musicians and Chair of Jazzlife Alliance (NI).

Nigel Tully MBE (1961, Physics) is co-founder, bandleader and singer/guitarist with The Dark Blues, one of Britain’s most popular party bands. Their career highlights include Royal Family private parties at Buckingham Palace and Windsor Castle, and working with Phil Collins – who played alongside the band at HRH Prince Charles’ 40th birthday and then asked them to play for his wife’s party in Geneva on Millennium Night. Nigel formed the band (originally known as The Fourbeats) while a student at Univ in the 1960s. He has made over 5,000 appearances in over 50 years as the leader of the band. They have played at, among other venues, the Savoy Hotel, Claridge’s, Cliveden, Spencer House, the Natural History Museum, Blenheim Palace and Hampton Court Palace. Nigel is also Chair of the NYJO (the National Youth Jazz Orchestra of the UK), Pastmaster of The Worshipful Company of Musicians and Chair of Jazzlife Alliance (NI).

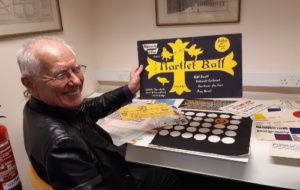

Nigel kindly donated a collection of ephemera relating to The Fourbeats to the College last year, including posters from gigs at Univ and around Oxford, programmes and an EP. Dr Robin Darwall-Smith, College Archivist, arranged for the posters to be restored to their former glory. We invited Nigel to tell us about the early years of The Fourbeats and his adventures in music since.

I turned up at Oxford in 1961, having taken my prelims, so not needing to do any work – or so I thought. I’d got an electric guitar and I read the NME (New Musical Express) and would check who was number one in the charts, which was what you did in those days. Nobody in Oxford had the slightest interest at that time. Oxford was completely jazz-oriented. It was seen as rather low to take an interest in popular music. We were all influenced by folk, but Oxford undergraduates had a fantastically narrow view of music. I might have been the first person to go to Oxford University owning an electric guitar and steeped in that music.

I’d left school at Christmas having got my scholarship, so I had nine months before I came up. I found a drummer and two guitarists, and by the time I got to Oxford in late September, early October, I was doing three gigs a week in Birmingham, all pop music. I was playing the British musical influences of the time who were the American rock and rollers – people like Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, Buddy Holly, Elvis, Bo Diddley, even James Brown. Those were my heroes.

We practiced mainly in the Univ Music Room by the Shelley Memorial and occasionally in my rooms. In my first year, I was in 83 High Street and in my second year in lovely rooms on the first floor in Radcliffe Quad. John Albery, who at the time was just a don but later became Master, was on the next floor down but said he didn’t mind me playing.

The Fourbeats, Nigel Tully’s scrapbook

There was a guy called George Adie (1960, PPE), a jazz guitarist who said he would give me lessons. He was in an Oxford band of the time called the Swing Sextet, and they played jolly trad jazz, they had a trumpet and a saxophone – instruments I had no idea about. In May 1962 they had a gig out at the Vicky Arms, a pub up the Cherwell, and George invited me to come along to see what a real band does. I watched them playing their jazz. When they took a break, he said to me, “We’re off to the bar, why don’t you use my guitar and play some of your silly pop songs.” So, I got on the mic, and I started singing stuff like Blue Suede Shoes and Johnny B. Goode on my own. The Swing Sextet were not asked back. The audience liked this nice, easy stuff. I had tapped a sort of hidden vein of people liking pop music, but not being sure they were allowed to admit it!

At that point, I thought I could now form a band. One of the first people I met was Ray Blazdell (1961, Classics). I knew him as a trombone player, but he was really a pianist. He said he really liked jazz but I said that I’d got a gig on Saturday night, somewhere outside Oxford. And we were getting 10 quid, so I could pay him two quid. I asked him whether he knew Blue Suede Shoes? And he said he did, and he knew the B-side too, which is Lawdy Miss Clawdy. It’s got a nice piano part. So off we went to this gig and at the end of each number, we’d look at each other and say, “What should we do next?” We’d never rehearsed, but we knew the same tunes. We knew Chuck Berry and we knew Elvis and Little Richard. I would say let’s do Tutti Frutti, let’s do Long Tall Sally. I’ll do it in C – I’ll start!

At that point, I’d never had a lesson in my life. I’d learned from other guitarists. You’d sit in your room and show each other how you finger a chord. This is not false modesty – I’m not a very good player. I’m a very ordinary guitarist. I used to be quite a good singer – though my voice is not what it was – and I was a good bandleader. I knew how to make the band work and I knew what to make the next song so that people would dance. So that was my tiny little talent for what it’s worth.

The Fourbeats, Nigel Tully’s scrapbook

Most bands in our game go on stage with a setlist, they know what they’re going to do. That makes life easier because everyone knows what they’re doing. The Dark Blues are different – we never have a setlist! I get to the end of a song before deciding what the next will be, but there are no gaps – we have great continuity. For example, at most of our gigs, we play Adele’s Rolling in the Deep these days, it’s a great tune and Annabel Williams our singer does a wonderful job. I start it on my own on the guitar, so I don’t bother saying to the band we’re doing Rolling in the Deep next, I just start it.

I knew the theatrical people at Oxford and one of them in the ETC (Experimental Theatre Club) was a guy called Doug Fisher. Doug eventually joined The Fourbeats on rhythm guitar, he was at Keble. He had a very nice high voice and he could do the highest harmonies for things like the Beach Boys and the Searchers, and he was very funny too. He brought in Annabel Leventon (St Anne’s), who was the queen of OUDS. You’ll see on some of the publicity sometimes it was “Annabel Leventon and her band.”

Petula Clark once decided to come to Oxford and record a French TV show here – and did it with us. Pet later had a real comeback with a record called Downtown, a big hit, and I was in the studio in the control room as her guest when she recorded that, and it was such a thrill.

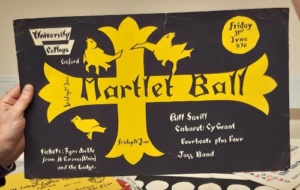

The Martlet Ball featuring the Fourbeats

We played a lot at college balls. We were playing with people like The Who. I also remember playing with Cream and stepping over Ginger Baker’s prone body on a Merton staircase. In those days, bands played together at the end of the gigs. At the Univ Ball in the summer of ’64, the other bands were Spencer Davis with Stevie Winwood and a band called The Nashville Teens, who had a hit with a great song, Tobacco Road. At the end of the night, 12 of us were on stage doing What I Say at four o’clock in the morning in Univ Hall. The night before we’d been at Oriel with The Hollies. They’d just gone top of the hit parade with Just One Look and we followed them on stage.

We were not in the same league as these people. These were big international names and people selling lots of records, but we all loved the same American rhythm and blues. We’d all had the same heroes and we’d all sat in our bedrooms, practising along to Chuck Berry, Little Richard, Eddie Cochran, and so on. We all worshipped the same heroes. By the summer of ‘63, this music was everywhere.

Over a period of about six months, I hired and fired musicians for The Fourbeats because all I wanted to do was play at dances. They might be in the Union cellars, or at the Queen’s Beer Cellars, or the Newman Rooms, at an Eights Week ball, a start of term event or something else. Eventually, I’d got a fixed band. I’d got Ray Blazdell on piano, Ross Treliving (Pembroke) on bass guitar and a drummer called Pete Morgan from Trinity. So that was the band, along with Annabel Leventon and occasionally Doug Fisher on rhythm guitar. That became set personnel for quite a while.

We got introduced to a woman in London called Lady Elizabeth Anson, a British party planner to rock stars and royals and a cousin to the Queen. We ended up being a London-based society band, playing pop music alongside old-fashioned waltzes and quick steps, rumbas and cha chas and tangos. Slowly, over that early sixties period, we became very familiar with the back entrance to the Grosvenor House and the Dorchester and the Savoy and the Hilton and the Ritz. I couldn’t believe it. I’m a northern grammar school lad from Leeds. And I was being paid to play the music I loved. In the daytime, I had a lovely day job with IBM and they were quite proud of me. They were genuinely very supportive.

Autumn Hop poster featuring The Dark Blues

Where did The Fourbeats end and The Dark Blues start?

I’d found a flat just at the top of Harley Street and I was talking to Peter Morgan, the drummer. He’d read law and he was articled to some solicitors in Reading. He said he was going to keep going in the band as well. Ray was still at Univ and Ross was still at Pembroke reading English. I said to them that I didn’t think The Fourbeats was a great name – we need something, and we’ve only got one gimmick, which was that we were all at Oxford. I suggested we change our name to The Dark Blues. People will ask why we’re called The Dark Blues and you tell them that we’re all from Oxford. In those days people booking my sort of band expected you to turn up late, get drunk and swear over the microphone. But we wanted to convince them that we wouldn’t do that at their lovely daughter’s 18th birthday party in the family castle. That’s why we changed the name. We got some very good publicity out of it.

The next big thing that happened was that Lady Elizabeth Anson called me and said she had a very important client and wanted us to audition for them. She said she couldn’t tell us who the client was, but they lived west of London. I said to her I was sorry, but The Dark Blues didn’t do auditions, but I’d meet whoever the client was and explain to them why auditioning was a bad idea. I met someone who turned out to be the Queen’s Equerry (and Deputy Master of the Household of the Royal Household). He said he was organising a party for a young friend of his and gathered I didn’t want to audition. I said, no, and explained why. He said, “You sound as if you know what you’re talking about and I’m going to book you.” That was Princess Anne’s 18th birthday party at Windsor Castle. We also played at Prince Charles’s 21st. People ask how we got that gig and I say, “It’s easy, his sister recommended us.”

We did about seven gigs altogether for the Royal Family. Once, we were in the music room and The Queen and Prince Philip appeared to watch the fireworks from behind the curtains. Prince Philip came and stood next to me and started talking – he’d got the common touch. He said: “The Dark Blues? Which college were you at?” and I said, “Univ Sir. Aren’t you an Honorary Fellow?” And he called out to The Queen – “Nigel’s a Univ man.”

At another event I’d got my guitar around my neck and the drummer was at the drum stool, and The Queen walked in and turned to Prince Philip and said something like, “Oh look darling, it’s The Dark Blues, how good,” and she came up and asked if we could play a Charleston. There wasn’t a minute to say, “Um, er.” I might have been beheaded! Of course, she danced. Then, other people came in and we did what we always do, which is not have a programme. I think we charged The Queen 75 guineas.

Another time, a chap comes up at the end of one gig and said he was Head of the Household for King Hussein of Jordan, and he wanted to get us over there to play. We ended up playing there twice. King Hussein is the most charismatic person I’ve ever met. I have a photograph of him and written on it in his handwriting is “To Nigel Tully with my thanks and best wishes.”

We made our first recording as The Dark Blues in 1983 and we called it Overdue because it took us that long. The problem is we didn’t write our own material – we play covers of other people’s songs. You can see why people would book us to play at their party, but why would they buy The Dark Blues’ version of Satisfaction? We did an album in 1988 called 25 and Going for Gold for our 25th anniversary, and I wrote a song called 25 Years and it’s the only piece of original composition I’ve ever done. I thought, “I need a song that talks about this band that’s 25 years old.” I woke up at 4 in the morning and I said to my wife, “I’m just going downstairs to write a song dear.” I came back an hour later and I’d written it. It’s the story of The Dark Blues.

To hear The Dark Blues visit their website or Soundcloud.

This feature was adapted from one first published in Issue 14 of The Martlet; read the full magazine here or explore our back catalogue of Martlets below:

Published: 18 March 2022