China: Land of Extremes & Contradictions

David and Lois Sykes Scholarship to China Travel Report – Sage Goodwin (2017, DPhil History)

David and Lois Sykes Scholarship to China Travel Report – Sage Goodwin (2017, DPhil History)

Thanks to the incredible generosity of the David and Lois Sykes travel grant and the very kind administrative help of Louise Watson, in April 2019 I travelled to China alongside my friend and History of Art DPhil student Sylvia Alvares Correa to visit fellow Univite Barclay Bram Shoemaker. Barclay, whose Area Studies DPhil project is an ethnography of approaches to mental health in China, was based in Chengdu for the year conducting fieldwork. After seeing his Martlets talk on Chengdu’s Jianchuan Museum Cluster and the commemoration of the cultural revolution I became intrigued by the cultural impact of Communism. My History DPhil on television news coverage of the black freedom struggle interrogates democracy narratives and the American national self-imagination. The opportunity provided by the Sykes fund, to compare and contrast how a diametrically opposed belief-system has shaped a society, combined with a willing Mandarin-speaking guide and host was too good to pass up. Throw in an enthusiastic travel partner with a penchant for secular pilgrimages (Sylvia has literally co-founded Oxford’s Pilgrimage Studies Network) and it seemed the stars truly had aligned.

Prepping and Packing

For anyone looking to travel to China I have two main pieces of advice. Firstly, download a VPN. Many of the digital amenities that have become part of the fabric of our twenty-first century Western daily lives are blocked in China. Feel like checking something on Google? Blocked. Need to message someone on Whatsapp? No chance. Want to waste a few seconds scrolling on Instagram? Forget about it. If you’re in the market for a digital detox, travelling to China would be a good move. Rogue and nonsensical, sure, but effective nonetheless. Of course, China has its own alternatives to all of these services but it can be tricky as a non-Chinese citizen to access some of them and the Chinese state has what you might call a cavalier attitude to an individual’s right to privacy. Luckily, for those who don’t want to try their hand at orienteering with paper maps or recreate the dark ages of early 2000s family holidays where crossing British border meant an enforced communication cut off, there is another way. The nice people at Oxford IT Services have solved all of these problems by providing a VPN with easy to follow instructions for laptop and mobile download. On top of that at Beijing airport there are kiosks which will vend you a Chinese SIM card with a plentiful data plan. This small bit of preparation will make your life travelling in China immeasurable easier. And how else are your Facebook friends going to know what you’re up to?

Secondly, do not take the visa application process for granted. As someone blessed with a passport that allows me to freely roam the European Union and waive the American visa system with just a few clicks every 2 years, I had been lulled into a false sense of security. It turns out the Chinese government are pretty nosy about your past whereabouts from the moment you were born. Taking a turn towards the Kafkaesque, they also want proof that all your flights and accommodation have already been booked before you’ve made the visa application. Make sure those are refundable in case something goes wrong. And you had better leave enough time to make the application before your scheduled trip. For the sake of your blood pressure, learn from my mistakes.

After some frantic high drama with the Chinese Visa Center, and armed with our newly downloaded VPNs, Sylvia and I were on our way.

Sights and Sites – Beijing

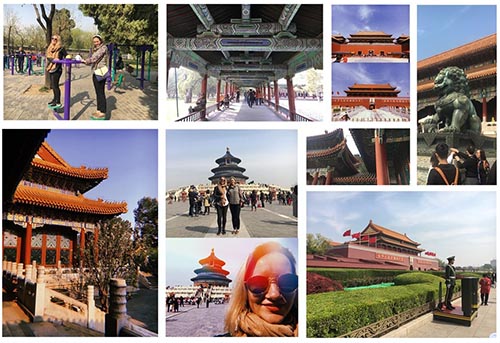

We began our trip with a visit to Beijing. We decided that if we were travelling all the way to the other side of the world we couldn’t not go to the People’s Republic capital. Although we had a very limited time there we got a lot of bang for our buck. This included a one-day tour with a private tour guide taking in some of Beijing’s greatest hits. Sylvia’s brother and father had previously visited the city and had specifically recommended their guide Maggie. Luckily, she was free. Our first new friend in China was lovely, extremely knowledgeable, and very interested in Sylvia’s brother’s relationship status.

A lot of people may prefer to explore the city on their own, but given our time constraints a guided tour was perfect for us. It also gave us a chance to find out more about what life is like for a modern working Beijinger and Maggie was happy to answer all of our questions. We began with the Temple of Heaven, where apart from the beautiful architecture and astonishingly ornate, hand-painted, decorative finishings, we were struck by how different life must be for the elderly in China. Sylvia and I followed Maggie past large groups practicing Tai Chi, working out on public exercise equipment, and playing cards and board games together around the park. Coming from a country where loneliness has reached epidemic levels, especially amongst the elderly, this public communal sociability which seemed partly promoted by the government but mainly an ingrained part of the culture, was eye-opening.

Next we headed over to Tiananmen square and the Forbidden City Palace Complex. Tiananmen Square is probably the strangest place to visit as a Westerner. The unnervingly benign painted half-smile of Chairman Mao gazes down at you from the preposterously large portrait overlooking the giant parade ground. Looking up at him, you can’t help think of the Communists’ brutal crushing of the 1989 student protests that the words Tiananmen Square have come to stand for – in the West. The Chinese government suppresses any information about this flashpoint in twentieth century history. It is therefore far from common knowledge for the Chinese. In this one instance, presumably the knowledge gap between us and our otherwise clued-up guide was reversed. Passing through the gates of the palaces we chose not to dwell too much on it. Instead we skipped further back in History to the Ming and Qing dynasties, replacing the green-uniformed guards patrolling the square with the jade guardian lions that protected the palace buildings.

Our final stop of the day was the beautiful lakes and gardens of the Summer Palace, where Sylvia and I both could have easily spent an entire day in its peaceful blossom-filled tranquillity. It was here, in the decidedly less serene crowds of the public bathroom, I experienced two rites of passage of being a Western tourist. Firstly, while being jostled in a queue that operated on a logic all of its own, I had my photograph taken by two cleaners. They wordlessly but charmingly were very insistent that I pose next to the total stranger in front of me who also happened to be blonde. I was then immediately presented with my first squatting toilet. I like to think I handled both situations with grace and aplomb.

While in Beijing we also hiked the Great Wall. We decided to attempt to go beyond the beaten track – if the walkways of a wall that has existed for hundreds of years and experienced billions of footsteps can ever be anything but a beaten track. A friend of Barclay’s organised a private driver to take us a few hours out of the city to a part of the wall less frequented by tourists. We were now fairly practiced at communicating without the spoken word but it was still a leap of faith that both us and the driver were on the same page about our understanding of the day ahead. It turned out that we were, more or less, and he delivered us to a village seemingly in the middle of nowhere to begin our ascent. This part of the wall was definitely less beautiful than photographs I have seen of it in Beijing, and certainly less safe (parts of it were literally rubble), but it was still very cool and a wonderful experience to be able to hike free from crowds. Sylvia was close to a numinous experience.

Up to that point my hiking history had largely been confined to climbing mountains (only Table Mountain and Lion’s Head to be precise) so the rises and falls of the wall with a total lack of final destination was new for me. Sylvia, the practiced pilgrimager, was far more au fait with a joys of the journey approach rather than a focus on the end goal. Climbing the wall turned out to be an entryway into some philosophical ideas sharing that we both enjoyed. Forgetting to take my laptop out of my bag before the four-hour climb, however, was a mistake. You live and learn.

During this part of the trip we also had a flying visit to Heibei Province. Barclay, knowing that we were coming from the land of overcrowded libraries, figured we might get a kick out of the world’s loneliest library. He organised for his friend Kristen (of Great Wall driver recommendation fame) to take us to Beidaihe, an exclusive beach resort in Heibei province that also boasted the cutting-edge buried in the beach art gallery UCCA Dune, and pulled some strings to get us in. We met Kristen at the anything but lonely Beijing station and began our quest to see just how isolated these books were. Quite, it turned out. Perched on a flat expanse of desolate beach, the library’s angular architecture seemed like it belonged in a Lemony Snicket novel. The reading room inside had very trendy armchairs that faced enormous plate-glass windows overlooking a bleak and interminably flat sea. The set up offered readers the choice between the rich imaginative worlds on the page or a vast expanse of nothingness. It was strange but beautiful.

For those who don’t worship learning but were down with the aesthetic, the one room church a couple of kilometres down the beach offered an alternative. Its absurdly pointed A-frame and bright whiteness looked like they came straight from Brett Helquist’s pen. Despite a series of unfortunate events (lost train tickets; the discovery that the UCCA Dune was still more concept than creation as it didn’t actually exist yet despite many images online; and a few sense of humour failures), I can safely say that our day-trip to Bedaihe was a once in a lifetime experience. It’s highly unlikely I will ever again find myself in an eerily deserted Chinese beach resort trying to find an art gallery 6 months too soon.

Our time both in, and mostly a few hours outside of, Beijing at its end, we hopped on a high-speed train and high-tailed it to Chengdu. I would highly recommend trying out the train if you’re travelling around China and want to get a sense of the countryside. It gave us the opportunity to take in a huge amount of the incredibly varied Chinese landscape. Including staggering amounts of newly planted trees. By the end of the journey Sylvia was ready to convert to Communism so impressed was she with the State’s ability to implement a reforestation plan. I hypothetically clung on to my democratic freedoms, focusing on the fact that these trees were only being built to combat China’s huge self-inflicted pollution problem.

As well as a view of the Chinese state’s impact on the land, our train trip also left us with a much more tangible understanding of the country’s vastness. Over our 10 hour journey we averaged a speed of 200kph, covering almost 2000km. That’s the equivalent of travelling from London to Bucharest. On most maps Chengdu looks like it’s right next to Beijing. China is really, really big.

Sights and Sites – Chengdu, the 15 Million Pop. City I Had Never Heard of

If you’re a panda aficionado you may have heard of Chengdu. Despite its being home to the Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (more on that soon), 15 million much smaller and less hairy inhabitants, and, over 260 Fortune 500 companies, I had not. This may be testament to my shocking personal ignorance, sure. Or my lack of appreciation for monochrome bears (reader, I’m now a convert). But I think it also speaks to how little we in the Western world actually know about China – a theme that came up again and again on this trip. Given that this country looks set to have a life changing impact on our lives in the West in the imminent future, it’s a sobering thought that most of us know almost nothing about it beyond Cold War stereotypes. Most of us, not including Barclay that is.

Having previously lived in Chengdu for his Masters research, and fluent in Mandarin Barclay was now basically a local making him the perfect person to show us around. Furthermore, alongside being a DPhil candidate and general swell guy, Barclay has many other talents. Among them is his journalism, where he specialises in writing about technology and society in China. This meant that our tour of all the must-sees and hidden secrets of the city went hand in hand with a contextual analysis of Chengdu and Chinese society, how it is being shaped by the lightning speed of technological progress, and the dystopian possibilities this progress has for the future. What more could you ask for?

These elements were encapsulated in the surrealism of our first day in Chengdu. China has taken the concept of organising your life through your phone and sprinted with it. One single device, or more accurately one single app on that device, WeChat, is the one stop shop for your entire existence. As well as an all-encompassing social media platform, think Instagram, facebook, twitter, and youtube rolled into one, it can be used to orchestrate every element of your daily life as a result of WeChat Pay. From ordering taxis, to making reservations, and ordering and paying for food ahead of time, WeChat has you covered. Barclay sometimes forgets to take his wallet out with him back in the UK, so obsolete has it become to his Chinese life.

From the moment we left his apartment on our first morning in Chengdu, Barclay was able to engineer every element of our day without once breaking the flow of conversation. As we got deeper and deeper into a discussion about the histories, meanings, and discourses surrounding the concept of Wellness in the East and the West, taxis pulled up out of nowhere wordlessly whisking us to our next destination. Waiters ushered us silently to tables ready waiting for us upon our arrival. Pre-ordered food arrived instantly as we sat down. Compared to the endless broken conversations and struggles to find a taxi that Sylvia and I had endured in our WeChatless existence in Beijing, it was like being in an Alejandro Gonzales Innaritu movie. Our day was a dream sequence. We moved around the city from temple to market to artist studio in one continuous take. I don’t think I’ve ever experienced such a pure and unadulterated lack of interruption. We had caught a glimpse into the future of hyper-convenience. On the one hand this was great as it meant that the debate we were having evolved much further than it would have otherwise. But it also meant that we never actually interacted with any of the people that played a part in our day. They were mute extras relegated to the background, who never had speaking parts.

Chengdu’s people are the most interesting thing about it (apart from the Pandas, reader, we’ll get there). According to Barclay, the Sichuan province capital has the reputation of being extremely laid back. You can see the manifestations of this relaxed attitude expressed through a counter-culture that has risen above the underground like nowehere else in the People’s Republic. Tattoos, a taboo in most other places in China, are relatively common here. There’s a nascent hip hop scene. Many artists have congregated in Chengdu drawn to the lower rents and less hectic pace of life, including Barclay’s charming friend Xie Fan whose studio we visited during our dream sequence. As Barclay told us, if the 4,200 coffee shops that have opened in the last 2 years are anything to go by, people here love to chill. Although that stat in itself reminds you of the relativity – chilled out by Chinese standards.

In one of those coffee houses we met Barclay’s friend He Yujia. Yujia is a phenomenally successful and prolific academic interpreter and book reviewer. Last year three of her translations were published, including – excitingly for me – ‘The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power’ Robert Caro’s first volume of the LBJ biography. As I’d spent a chunk of the previous summer at the LBJ presidential library researching for my dissertation and had visited both LBJ’s ranch and childhood home, we had a lot to chat about. As well as the finer details of the 36th American president’s rise to power, we discussed Yujia’s working life and the key to her huge success at the ripe old age of 32: what can only be described as an intense work ethic. Yujia is at her desk by 5.30AM most days and regularly puts in 14-hour shifts of pure mental concentration. (I can’t speak for Barclay but I continued to ignore the looming 100,000 words of my dissertation that remain largely uncommitted to paper, or word document, as it were. Post-China Sage’s problems.) Despite this super human work ethic, Yujia and her husband are children of Chengdu and were therefore happy to hang out with us for an hour or two to shoot the breeze over a cup of coffee.

While the culture may be more relaxed, industrial and economic progress, like Yujia’s next translation project, is hurtling ahead. As we looked out from the balcony at Barclay’s apartment one morning over JinJiang, Chengdu’s business and retail centre, he told us that a 400m skyscraper here is usually built in less than 2 years. Immediately below us the Daci temple now morphs seamlessly into the Taikoo Li luxury shopping precinct. ‘Nice temple and fantastic shopping mall’ exclaimed one TripAdvisor review I read, seemingly without a hint of irony. It may seem like a total contradiction the almost absurd juxtaposition of lives devoted to the ascetic with those determined by aesthetics. However, Buddhist and bargain hunter alike seemingly had no qualms about sharing their holy places each in pursuit of their own religion.

Chengdu is also apparently famously LGBTQ+ friendly. Although LGBTQ+ friendly here may mean something slightly different from our standards in Oxford, the city has a relatively high tolerance for alternative lifestyles. In the rest of China, not so much. The Communist state’s intolerance of homosexuality and the insidious ways this played out were thrown into stark relief one day when Barclay was using his phone to explain to me the complexity of Mandarin familial referents.

In Mandarin the word used to describe a family relationship differs depending on the gender of the two people involved, which side of the family the person falls on, and their relative age status be it younger or older. You can download a handy app where you input the relationship and it calculates the correct word to use. Barclay tried to enter an example along the lines of ‘My wife’s younger male cousin’ to demonstrate this for me but the app wouldn’t generate the word. After a few more failed attempts at figuring out what we might call his hypothetical wife’s extended family, a message flashed across the screen stating that in the People’s Republic of China same-sex marriage is illegal. Barclay’s app, it dawned on us, had him set as female. It was chilling to realise that even language was so closely policed and restricted. Despite all of Chengdu’s hipsters and chilled vibes, incidents like these every so often were a reminder of the inescapable harsh realities of life under a dictatorship.

However, there were elements of the Communist state to be enjoyed. Amongst them a cornucopia of public educational and recreational activities. Barclay’s Masters project on the Jianchuan museum cluster, the home of China’s largest private collections of artefacts just one hour outside of Chengdu, had first peaked my interest in visiting China. The sheer volume of ephemera displayed across its 32 individual museums is breath-taking. Chengdu itself also had a museum everywhere you turned. And in every one, once you’d had your fill of Chinese art, culture, and history there was an equally interesting garden to stroll through. During our time in Chengdu we visited our fair share of public parks, a staple in Chengdu, filled with ponds, gardens and teahouses. The crowning glory of all of these was the expansive People’s Park in which we managed to get lost and spent an hour trying to find each other. Of all our outdoor adventures, my personal favourite was the Bonsai garden at the Wenshu Yuan Buddhist temple. Hundreds of years of history contained in the dinkiest of delicate trees.

And finally, (apart from the food of course, which gets its own section below) the Pandas. The Pandas were wonderful. As I mentioned above these giant bears weren’t high up on my favourite furry animal list – I’m more of a cat person. But they were damn adorable. And the facility itself was really impressive. I hadn’t done any research on the Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding and with some vague and admittedly orientalist ideas about Chinese attitudes to animal welfare I didn’t have very high expectations. But the place was great. There wasn’t a cage in sight. The design of the park meant that the enclosures managed to allow excellent views of the panda enclosures in such a way that you didn’t feel like the pandas were at all compromised. They munched on mounds of bamboo or occasionally rolled over and yawned entirely undisturbed and evidently unperturbed. Another feat of Chinese engineering.

All in all, China’s most chilled out city and the most chilled of its chilled out inhabitants did not disappoint.

Tastes and Treats

Lastly, and most importantly, the food. Our culinary experience in China deserves its own special section. The flavours and textures I encountered defined my trip and remain my most vivid memories.

The first meal on Chinese soil was an accidental but nevertheless resounding success. Straight off the plane and unable to sleep in an upside-down time zone, unlike Sylvia whom I left snoozing in the hotel, I went for a wander around the streets stopping at the first dumpling place I saw. This turned out to be Din Tai Fung, a restaurant at the top of the dumpling list for everyone who had given me Beijing recommendations. Their signature Xiao Long Bao, soup dumplings, were out of this world. The culinary adventure had begun.

As well as some worryingly good train station fast food, Beijing was memorable for its Peking duck – a must for anyone thinking of visiting the city. I mean the duck, but I also don’t not mean the train station fast food. Barclay had written an article about the best duck restaurants in Beijing for Munchies, Vice’s food segment. So armed with insider knowledge we went to Si Ji Min Fu or ‘Mass Foodies Roast Duck’ as the English sign said. That was about all the English that we experienced during our Si Ji Min Fu escapade. We somehow managed to order a selection of food including the signature roast duck that chefs dotted around the restaurant floor were preparing to be plated. Sylvia was brave enough to tackle the duck head, I remained very content with my share of delicious duck pancakes.

Through Barclay’s article we knew the bona fides of the restaurant’s duckologist, the chef’s duck roasting philosophy, and exactly where and how his Peking duck fits into the history and culture of Beijing’s signature dish. However, it was no help in figuring out what to do with the strawberries on ice that inexplicably appeared at our table before any other food arrived. I’m still not totally sure if we were meant to eat them or not.

Our food odyssey began in earnest once we arrived in Chengdu. Barclay, when he’s not working on his DPhil, or writing his articles for Vice and Wired, is also a Chef. He therefore knows all the places, from fancy restaurant to street side hole in the wall, to taste the very best Chengdu had to offer. Considering its been named a UNESCO city of gastronomy, the offerings were pretty good. And we gave tasting all of it a college try, especially the street food. Pineapple on a stick seemed to be a market stall staple. And the Guo Kui street sandwiches were amazing. From gyoza to grass jelly, we had it all.

For me the MVP was a dish called Tian Shui Mian, or sweet water noodles. These thick udon noodles were salty, sweet, and spicy all at the same time. And they were the perfect way to experience the Sichuan pepper, a taste and physical sensation that has no equivalent in Britain. It’s kind of like licking a battery – in a good way. The only downside to the otherwise complete perfection that is Tian Shui Mian, is how difficult the unruly noodles are to eat for someone as inept with chopsticks as me. Inevitably, this meant much splashing of soy sauce. It brought to mind the carnage of when a friend of mine came dressed to a costume party as a squid. Armed with miniature soy sauce bottles he’d collected from takeaway sushi boxes in preparation, he deployed his ‘ink’ at unsuspecting victims. My attempts to tackle the Tian Shui Mian resulted in a similar redecoration of the furniture. A small price to pay for the salty, spicy, sweet goodness I still dream about.

A trip with Barclay to the enormous outdoor food market was a particularly eye-opening experience and not one for the squeamish. I saw more dead animal parts than I knew it was possible to eat. And watching a man kill a fish by slapping it on the floor before he sold it to us was fairly jarring. The fish continued to occasionally flail around every so often in its plastic bag coffin on our walk home. Although disconcerting, I think it was a valuable experience to see exactly what our meal that night had been through before making it onto our plates.

Desserts in Chengdu were a whole different kettle of fish. Not literally. But a lot of them did have the gelatinous texture and appearance of frogspawn. This jelly substance is apparently created from rubbing grass seeds together. The soft jelly texture combined with a sweetness that was both watery yet sickly sweet made for another novel culinary experience unique to our Chengdu adventure.

Alongside the actual cuisine itself, I really enjoyed the culture around the way meals are eaten in China. I don’t think there was a single meal we didn’t share. Our breakfasts, lunches and dinners were always a constellation of tiny plates that moved constantly around the table. Comparatively the plates of our individual main meal approach in the west are stationary lonely planets. As someone who is filled with existential dread at the prospect of pinning my colours to the mast when it comes to making a choice from a menu, the panoply of foodstuffs at every meal was both a relief and a delight. More importantly, it meant that every culinary experience was communal and eating was just as much about the company as it was about the food.

While I may not be ready to move to China tomorrow, unlike Sylvia, this trip was a once in a lifetime experience. I learned a lot about a part of the world I now realise I knew next to nothing about and it shattered a lot of misplaced preconceptions I had. There’s a lot we can learn from the People’s Republic about community. At the same time, it felt like a trip into our technological dystopian future and highlighted some of the dangers of completely unbridled progress. I came back with a renewed appreciation of the freedoms I take for granted in the UK, even if there are no sweet water noodles here.

An enormous thanks to my stars, Barclay, the host with the most, Sylvia, my eternally enthusiastic travel buddy, and the beneficent David and Lois Sykes Travel Grant for aligning so perfectly to make this trip possible.

To view a selection of Sage’s travel photos click the image below (PDF opens in new window)

Find out more about the range of travel grants and scholarships available to assist Univ students on our Travel Grants page or read further travel reports.

Published: 16 January 2020

Explore Univ on social media