Roy Park Memorial Dinner

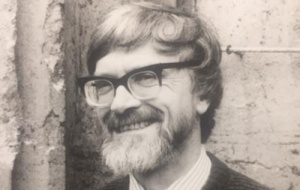

On Saturday 18 November, ex-students and colleagues, friends, current members of college and Roy Park’s family gathered for a tremendous dinner in hall to remember and celebrate the life and teaching of the famously unforgettable Glaswegian English fellow, who died in July 2019 at the age of 83.

On Saturday 18 November, ex-students and colleagues, friends, current members of college and Roy Park’s family gathered for a tremendous dinner in hall to remember and celebrate the life and teaching of the famously unforgettable Glaswegian English fellow, who died in July 2019 at the age of 83.

Speakers Luke Harding (1987, English) and Armando Iannucci (1982, English) both paid memorable tributes to their erstwhile tutor, conjuring his glorious, straight-talking, fierce but nurturing nature, through funny and moving memories of their personal experiences as undergraduates. To round off the evening, Dr Robin Darwall-Smith (1982, Classics), Archivist, read a selection of wonderful anecdotes submitted in advance of the evening by attendees: Hazlitt, cigar smoke, brown corduroy furniture that swallowed you whole, Romantic passions, unflinching respect for hard work and for truth — the essence of Roy shone through.

As Professor Helen Cooper, Honorary Fellow, who taught alongside Roy at Univ for many years, wrote afterwards: “Everyone talked about him with the same mixture of awe and affection — it was a wonderful occasion.”

As Professor Helen Cooper, Honorary Fellow, who taught alongside Roy at Univ for many years, wrote afterwards: “Everyone talked about him with the same mixture of awe and affection — it was a wonderful occasion.”

Thank you to Amanda Brookfield (1979, English) for this wonderful report.

The College is grateful to the many students, colleagues, and friends of Roy Park who have offered contributions in Roy’s memory (included below) to recognise his unwavering commitment to teaching and to the highest standards of academic achievement in the study of English literature. Please do get in touch with the Development Office if you wish to discuss this further. Martha Cass or Hattie Bayly would be delighted to hear from you.

Nick Smith (1976)

Here is an extract from my 2016 novel Drowned Hogg Day (pub. Justin Roseland Books). Although partly fictional, I’d say it’s also a fair reflection of my early experience with Roy. The other student mentioned, Philip Sherborne, is loosely based on the brilliant Old Etonian, Justin Broackes, who was the modest star of the 1976 English cohort. There’s some exaggeration for effect and, in the context of the novel, I’m trying to draw an analogy with the original encounters of P.B. Shelley and Thomas Jefferson Hogg. If anyone is interested in reading the rest of this Univ-based novel, it is to be found at https://drownedhoggday.wordpress.com/2016/11/10/thursday-10th-november-the-hoggblog-begins.

Besides all of us undergraduates, Roy was an inspirational teacher of doctoral students, many of whom went on to distinguished careers in academe and elsewhere. One of these was the future novelist, William Boyd, who was researching Shelley & co in the late 70s. Not long before my Finals in 1979, Roy (on sabbatical at the time) arranged for us to book revision classes with Boyd. I was the one finalist who took him up on that offer and enjoyed an hour two picking the brains of this very different Scottish Romanticist. Boyd won a JRF at St Hilda’s and it turns out I was the only male student he ever taught. He too has fond memories of Roy and sends his apologies from Venice that he is unable to make the Dinner. I wonder whether the character of Alex Murray in A Good Man in Africa (1981) (later played by Sean Connery) was, to some degree, inspired by Roy.

Roy’s favourite ex-student, as he revealed in unguarded moments, was the future Labour minister, Chris Smith, whose doctorate on Wordsworth and Coleridge was supervised by Roy in his pre-Univ days. I have a lot to thank the future Baron Smith of Finsbury for. As a 6th former, I applied to read English at New College but entertained little hope of making the grade. Quite by accident, I put down Univ as my 2nd choice and, when I arrived for interview at New in December 1975, I was summoned to Dr Park’s lair and treated to the full whirling dervish display, the flashing eyes and the floating hair. Despite my tongue-tied efforts, I found myself at Univ the following October. At the beginning of my first tutorial, Roy re-introduced himself and asked whether I preferred to be known as ‘Chris’ or ‘Christopher’? I explained that I always answered to my second name, ‘Nick’. The look of disappointment on his face was one that stuck with me, although it was many years later before I discovered why this revelation pained him. Still, I’m grateful to the more distinguished Chris Smith for his inadvertent role in sending me to Univ. Nominative determinism, indeed!

Lord Chris Smith

Roy was of course the most energetic, passionate, enthusiastic, and committed teacher, as I experienced when studying English under him at Pembroke College Cambridge. He was the most generous of friends. He loved and introduced me to Schubert’s late chamber music. But my fondest memory is of him sliding down the 3000 ft scree slope at the far end of Liathach in the Torridon mountains in Scotland, plunging downwards with increasing speed, just about surviving to the bottom of the mountain, and then turning round in bafflement to see me gradually picking my way gingerly downwards with far less brio. He did everything with real panache.

Derek Grant (1973)

At our first pre-term meeting he reviewed my entry into the college (I had only got three B grades at A-level) and stated, “I don’t care if you’re stupid – as long as you work!” (I think he was having some problems getting his undergraduates to attend tutorials and write essays…)

He once declared with fierce zeal, “Milton never wrote anything minor!”

Martin Reader (1986)

It was November 1990 and quite a crowd was gathering around the TV to witness history unfolding: Margaret Thatcher was resigning. Roy was no fan of Maggie! I cannot remember exactly how we got the message, but Jason Chess and I were summoned to Roy’s study. There waiting for us a bottle of champagne and three cigars – Roy was cockahoop and he had been saving that champagne for a very special occasion and was desperate to share it. And so we marked with Roy the changing of the guard. Whether or not a poet or a writer of prose was closer to the centre of his culture did not seem to matter.

Chris Thomson (1975)

I first met Roy at interview. I was sitting on an object with four legs, a seat and a back which I had unhesitatingly recognised as a chair. By contrast Roy and Glen Black each seemed to be reclining in the cockpit of a go-kart which had departed some time before leaving them stuck there. But then I’d just got off the train from Basingstoke, a universe away; maybe this was normal in Oxford?

And I was the one stranded. ‘Can you think of anywhere outside Shakespeare where this idea of nature can be found?’ Into my mind it sprang so I said it: ‘Er, maybe Strindberg’s Miss Julie?’ There was a moment’s hesitation the other side of the net and then another question was served. Idiot, I thought, that was clearly beneath all comment, never mind contempt….

Much later on Roy told me that in the course of my first term he and the College Chaplain had agreed that I rather resembled a half-trained Labrador puppy, simultaneously endearing and perplexing. Over subsequent years perhaps Roy, like me, came to wonder if he hadn’t hit on something true of more than just the gawky adolescent.

Tutorials with Roy were physically and intellectually daunting. Most unfortunately some salesperson had succeeded in persuading Roy that a mini, upholstered ski-jump was just the thing for sitting on. Getting down that low for someone of my height was impossible without either collapsing or else feeling that you were climbing into bed or preparing for prayer. Only when I baby-sat Kirsty one afternoon did I discover what Roy’s furniture was really ideal for: making dens and hide-and-seek with three-year-olds.

Once pinned in place by gravity and curvature of the spine my main technique, actually my only technique, for getting through the tutorial itself was not prayer but speed. Just get through the damned essay! One afternoon I was zipping along at a fair old clip when I was suddenly in collision with a resistant chunk of the Immortality Ode:

– But there’s a Tree, of many, one,

A single Field which I have looked upon,

Both of them speak of…

An ominously quiet voice interrupted: ‘You can’t say those lines quickly, can you?’

Flight-fight response kicked in. Fight? Who am I kidding!…the flight-response kicked in yelling Agree, agree, just agree!

‘Er no.’

‘Why not?’

Oh God…..then happy deliverance: ‘Because they’re all monosyllables?’

‘Yes, and why has he done that?’

‘Er, because what he’s saying is really important?’

‘That’s right. Don’t forget it.’

I haven’t, Roy. I don’t think I will.

What made Roy’s tutorials so demanding was that he attended to every word I said: ‘You don’t mean ‘dynamic’, you mean ‘kinetic’.’ I always felt he’d concentrated harder on my education in the course of an hour than I had throughout the preceding week. Nothing, nothing got by him. I suggested that Coleridge brought nature to life as if at the touch of a magic wand. Instantly, ‘Where did you find that?’ I didn’t dare say Out of childhood stories.

‘Er, I didn’t….I just made it up.’ Somewhere from behind thick lenses and a cloud of pipe-smoke Roy stared at me as if my papers might not quite be in order as he scanned everything he’d ever read on Coleridge for a magic wand reference. Finally, ‘Don’t forget it – it’ll stand out to a tired examiner in the summer.’ Phew. I was through.

Just before finals I decided to check out a particularly cherished thought by ringing up anyone who’d ever had the questionable privilege of attempting to teach me. What about geographical location as proxy for a spiritual coign of vantage in, say, Four Quartets, Tintern Abbey and Wyatt’s Satires? This provoked one endless silence, one sharp intake of breath, one rather weary Don’t do it!, and then dear Roy. I could picture him weighing up my idea the other end of the line. Hmm…maybe not as barmy as his one about Phèdre and The Graduate….Finally the judicious response: ‘It might work as viva bait.’

After finals I stayed on in Oxford becoming steadily more restless as day after day the results weren’t posted. Then a card came saying ‘You are dispensed from viva voce examination’. What did that mean? Round I went to see Roy.

‘Have you not heard the rumour?’ he asked.

‘No, what rumour?’

‘Well, I was at a drinks party on Saturday night with Jonathan Wordsworth, chair of the examiners, and he says you’ve got a First.’

The most enormous grin welled up within me and flowered extravagantly all over my face.

‘Two things, Chris. First, he’d been marking for a month and drinking for an hour so his word’s not reliable. Second, I don’t think you’re that good.’

I beamed at Roy.

Just stop grinning, I thought, You heard what he said. STOP GRINNING!!

I know that Roy forgave me the First because some years later I came across a reference he’d written for me. I’ve never known anyone who spoke and wrote so glowingly of people behind their backs.

Besides acquiring a real discipline about words from him I have what I regard as a very precious gift from Roy. It was sort of shunted towards me at a point when I think he must have been clearing out his Univ room: fifty pages of his key quotations from Aristotle to Wordsworth, arranged by subject and headed Romantic Perspectives, University College, Oxford; Michaelmas 1990. Prospero had bequeathed his book to – Trinculo. He knew many far worthier recipients. But I choose to think Roy’s gesture had nothing to do with appropriateness or aptitude. It was a gift to me and given – he would never, ever have admitted it – with genuine, grudging affection.

Richard Clegg (1977)

After reading my essay to Roy on Coeridge’s Conversation poems he commented briefly, “Richard you are disappearing up your own ers.”

As abrasive as sandpaper.

The following week, “That’s better.”

There were Oxford tutors and there was Roy.

Sarah McConnel (Drew) (1980)

If it is appropriate, could you let Alice Park know that I am writing a historical romance (which Roy might not have approved of) set in 1819 (which he might have) and featuring a cameo from Charles Lamb specifically in memory of Roy’s championship of him.

My father, Philip Drew, had taught Roy (at Glasgow University) and spoke often of his tenacity and scholarship. When I applied to Oxford, he encouraged me to consider Univ; “Roy Park will make sure you educate yourself properly.” Which he did, of course, but he did much more, in making critical reading both hugely enjoyable and a tool for evaluating motives. I was lucky to have known and been taught by him.

Jonathan Earl (1977)

Roy was the single most important figure of my Oxford life, and his influence has stayed with me ever since. I will never forget his brilliance, passion, wisdom, humour and deep support. Like many of his students, I started studying with Roy feeling daunted by his intelligence, but from this unpromising start we forged a strong and lasting bond. He was a truly great person.

Keith Budge (1976)

Roy made me work – he also understood that my involvement with university rugby meant that I sometimes needed latitude.

I was undeservedly helped in this respect by the great Dennis Kay (who was captain of the OURFC side and died tragically young) having been a star pupil of Roy’s a few years before.

Roy regaled me with stories about Dennis (arriving late at rucks and kicking people, which amused Roy) and thought that, who knows, I might follow Dennis to academic stardom. Not so!

Anyway, he was good to me and good for me and I feel lucky to have been taught and guided by him.

Final memory: advice – eat a salad before an afternoon exam. Response to stress: “I just dig and dig…”

Trevor Oney (1982)

Roy was obviously known for being very passionate about literature. So much so that during tutorials, mention of a certain a idea or subject would cause him to break off and expound at length and with great feeling about that particular issue, while we (the students) sat opposite him in silence with our half-read essays in our hands.

We once joked about this to Helen Cooper, who said ” I sometimes think I’d like to be a fly on the wall at one of Roy’s tutorials”. To which an American in our set responded, “I usually feel like I AM a fly on the wall during Roy’s tutorials.”

Made us laugh at the time. Not sure how funny it is 40 years later.

Mike Deriaz (1978)

I first met Roy when I was a 17 year old 6th former and I had come to visit Oxford and enquire about reading English at Univ. I had literally never been to Oxford before, so naturally I had a good scout around and ended up popping into Blackwells and buying a couple of books before my appointment with Roy.

When I walked into his room an hour later, he looked me up and down and immediately yelled “YOU’VE JUST MADE THE GREATEST MISTAKE OF YOUR LIFE!”

I was a little nonplussed at this reception, but he then explained in slightly more gentle tones, pointing to my Blackwells carrier bag: “You’ve just visited the most wonderful bookshop IN THE WORLD, and your life will never be the same again!”

Alison Pindar (Ali Mercer) (1991)

One of my most abiding and vivid memories of being a fresher at Univ is of standing at the bottom of the stairs that led up to Roy’s room, sleep-deprived, shaky with caffeine, clutching a just-finished essay on the Victorian prose writers, and breathing in the dense, lingering smell of his cigar smoke as I waited to meet my doom. His tutorials were the stuff that rites of passage are made of, not to mention panicky bonding with one’s fellow freshers. I heard that if you did really well the sherry came out, but it never did for me. However, I still feel gratified that he once said he liked my use of semi-colons, and I still think of him whenever a proof-reader takes them out.

He taught me much more about storytelling and writing than I realised at the time – quite possibly more than he realised, too. His voice often comes to me out of the blue from down the years – those quotes that he peppered our tutorials with, all those potential epigraphs: insights into narrative, character and motivation, time, memory, truth, imagination, loss, the bonds people make and break, what this costs them and what they owe. ‘If the past is not to bind us, where does duty lie?’ ‘The part of a man that he sacrifices in pursuit of a given aim comes back, years later, knife in hand, to sacrifice that which sacrificed it.’ I may be misquoting – if so, I hope Roy would forgive me. His teaching gave me tools that I am still learning how to use, but these days, I understand a little better how valuable they are, and how lucky we were. He pushed us to think and he put us on the spot, and we were left in no doubt that the work we were doing mattered.

Bill Quirke (1973)

Roy was in his second year at Univ, and I was in my first. I was shocked to discover after having thought Univ was going to be all Brideshead Revisited, that Roy actually expected you to work, and was unmoved by even the most creative excuses. Feeling unwell in my first term, during Hardy week, I was given a very casual note by the college doctor to drop into the Radcliffe Infirmary should I be passing. I was in the waiting room desperately trying to get through Tess of the D’Urbervilles, when they gowned me up and took me into emergency surgery for appendicitis. My only consolation when I came around was that I would miss my Thursday evening tutorial and I could give the rest of Tess a miss. At precisely 8 pm on the Thursday evening as I lay in my hospital bed, high on painkillers and relishing the reprieve, Roy suddenly materialised at my bedside to conduct the tutorial. There was a terrible gleam in his eye and a devilish smile on his lips as he watched me panic. Jude has never been more obscure.

This was in the halcyon days before Roy grew the beard, but after I discovered that his childhood nickname was, ironically, Curly.

We had our tutorials late on a Thursday evening under the lamp light in Roy’s room furnished with modern low-slung corduroy clad foam armchairs. As you read your essay into his unblinking gaze, you slowly slid down the slope of the chair losing whatever dignity Roy’s reception of your essay had left you. But strangely no matter the subject of the essay, whether it was ancient or modern, Anglo Saxon or Middle English, no matter the subject at hand or the period of history under discussion, Roy always felt Hazlitt had something to contribute.

If Roy had been in the unlikely habit of wearing a motivational wrist band, it would have said “what would Hazlitt say?“. It became increasingly clear that the man had a heavy Hazlitt habit. It was rumoured that at his wedding, when asked “Do you take this woman to be your lawful wedded wife?”, Roy had turned to Hazlitt for the answer. You began to suspect that Hazlitt had never given a moment’s thought to many of the subjects that Roy dragged him into, and although Hazlitt may never have consciously thought about any of them, Roy was there to tell you that at some level he definitely had.

Unfortunately as you read your essay in the gloom of his room, Roy had the unnerving habit of suddenly leaping to his feet, plucking a volume of Hazlitt from the bookshelves, to look for an apposite passage. And if he couldn’t find an apposite passage , he would read one anyway. Starting with a quiet intensity, in hushed and reverent tones, he began to read from the sacred text. As he read, he became more impassioned, but the more passionate he became, the quieter he got. Here was a man who could make quiet intensity all the quieter. Until, just as he reached his inescapable conclusion, he was completely inaudible. As he looked down at you triumphantly, you could only guess what he had been whispering . Of course, you learned to nod along enthusiastically, but what you most learned during that first winter term in his darkening room, was that if you wanted to match Roy’s enthusiasm, it paid to have good night vision and to be able to lip read.

Now I like to think that in some celestial seminar room, in hushed tones beneath the lamp light, Roy is passionately revealing to a grateful Hazlitt what the poor man truly thought.

Kirstie Hutchinson (1989)

I changed from Experimental Psychology to English after my first year, having realised that my desire to become a clinical psychologist was weaker than the siren call of literature. One of my fondest memories of Roy is sitting in Noughth Week of Michaelmas Term on the very low brown corduroy sofa in his room overlooking the High Street, feeling like a frightened rabbit as I tried to explain why I would like to study English and being told by Roy, in his gruff Scottish burr:

“Well, Miss Hutchinson, the thing is, your academic record is fine – but your decanal record is… appalling!”.

A number of people had recently been allowed to swap to English and so, in a bid to keep further riff raff out, it was decided I would need to write several extended essays and then sit collections on Joyce and the Middle English authors. Unfortunately, it was also thought (incorrectly, as it turned out) that my Local Education Authority would not fund a repeated first year, so after I had acquitted myself acceptably enough to counterbalance my allegedly appalling decanal record, I had to sit the rest of the year out and join the second year of the English course. By the time the mistake was discovered, it was too late.

My fellow second years didn’t seem to share my regret at having omitted Anglo Saxon…

My other regret was that only being able to spend two years on my degree meant that I did not have three years under Roy’s tutelage. He was a wonderful character with an infectious and readily communicated enthusiasm for Thomas Browne, Thomas Lamb and of course the great William Hazlitt, and shaped my mind in ways I could not in youth appreciate but which I now value immensely and gratefully.

Paul Hamilton (1972)

Confidential chats with Roy

“Sit down! Sit down! Where have you gone? Ah yes. Now, I want you to take some time off Paul. You’ve been working very hard. Well done! Glencoe? No? Ah well when Ian Jack let me take a break in Cambridge once, I managed three films a day. You have to have a programme! Also, recreational reading – a Dickens a day, easy! Learn a language. Have you read all of Tolstoy yet – that marvellous bit where Pierre realizes that in betraying a friend he has betrayed Christ. There’s an essay on the Fall in Romanticism hidden there, the grammar of Romantic rhetoric… But your holiday – you should write the holiday up, so we know what you’ve got done, then get back to work. Have you finished Howe’s Hazlitt yet? Only twelve volumes so far? C’mon! But you say you’ve only read the first two volumes of Coleridge’s Notebooks? And only one volume of Coburn’s Notes? And what about the ones still in MS in the BL? Plans? You’ll recall volume one, number 1766, about the pot of urine – I’ll just climb up and get it down. ‘What a beautiful Thing Urine is, in a Pot, brown yellow, transpicuous, the Image, diamond shaped of the Candle in it’. Marvellous to ‘admit a wide solution’ like that, not an abstraction in sight, although all ideas are abstract, as Hazlitt told us. And did you finish all these Scottish Enlightenment thinkers missing at the end of the last term? Think of John Bryce who read them all when he was blind, man! Still not read Kames, or Gerard? or Campbell? or Alison? Brown, Reid, Stewart and Price? Pure Kant Price is, though not Scottish! Holiday? Ah yes…!”

Alex Thomson (1980)

Roy wrote me a card just before finals nearing the inscription:

Best of luck. Just remember that the light at the end of the tunnel is the light of the oncoming train!

A year or two after graduation my first book – a travel book was published by Harper Collins. I sent Roy a copy as a surprise from Belfast where I was living at the time in the mid 80s.

Roy eventually responded detailing the security alert an unsolicited package from Belfast had caused, in some detail. He never did say what he made of the book.

Fingers crossed, hoping to be with you along with elder brother Chris, without whom I would probably never have met Roy really.

Beth MacNamee (1985)

Without Roy, I would not have been at Oxford. He understood the Scottish exam system and took delight in spotting likely Scots, scooping me up when my first choice college rejected me. He saw beyond my diffidence and naivety, and his wise guidance, exhilarating teaching, and deep seriousness about literature made a profound and lasting impact on me. He is the teacher who changed my life and I will never forget him.

Peter Topping (1978)

Roy never really approved of my commitment to college rowing.

“Will you have the time” he would enquire, concerned, worried, inquisitorial, all in one searching look from behind those astonishingly thick spectacles.

On the rare occasions where I was feeling confident that I had totally nailed that week’s essay, I would attend the tutorial in rowing kit.

More often than not, I would turn up suitably and modestly dressed, ready for an hour’s ducking and diving under a relentless scrutiny that revealed how little I really understood what Blake or Wordsworth or Keats really really meant.

I still have on my bookshelves the company of the Lake poets and their circle, and whenever I take down the Essays of Elia, or re-read Frost at Midnight, I think of Roy and that burning intensity of thought comes back to me from nearly fifty years ago.

And I am STILL rowing, currently on the wide and majestic Tyne rather than the trickle of a river at Oxford!

John Ballatt (1971)

I studied English at University College from 1971 to 1974, and was privileged to have Roy Park as my tutor. He was thoughtful, grounded and warm, tolerant of my waywardness as a much distracted student, and very supportive. My preference for bringing obscure Jungian and philosophical (even occult!) perspectives into my essays on the work of poets like Milton didn’t faze him. Indeed he encouraged my eccentricity.

He came to eat one evening at our student flat in Park End Street in my final year and was charming, down-to-earth and good company.

I remember to this day ringing him for my results from a phone box in the centre of town, in darkness and, as I recall it, torrential rain. He was angry on my behalf that I’d automatically got a third: ‘Your average mark was much higher, it’s just the rules about the number of gammas you got. I think I’ll complain!’ ‘No Roy’, I said, ‘it’s entirely my own fault, and my idleness deserves no better – and you were a wonderful teacher, so it’s me who’s let you down’. He swallowed his sympathetic, loyal frustration and we wished each other well. I wish we’d run into each other again as I sorted my life and subsequent career out, both to thank him, and to hear more of his thoughts.

What a fine and lovely man.

Richard Dance (1990)

I have so many reasons to be grateful to Roy for his friendship, his belief in me, and his many kindnesses. And I have so many fond memories, right from my first week as an undergraduate (his extraordinarily low furniture! the strong coffee! the tough love of the collection results pinned up outside his door!), to exam time (when we got carnations, and a good luck wave from his balcony!), to his genial twinkle at graduations. Thank you, Roy, for everything.

Emma Whiting (1987)

I had a lovely letter from Roy and Alice when they had retired up to Sutherland. He described so beautifully how he was spending his time watching the weather and rereading Dickens, and it gave a perfect sense somehow of a man resting after a job well done. I also wanted to note his wicked sense of humour, and how very entertained he was when we got stuff wrong! He was also very kind. But I did once turn up without having written my essay (Dryden week 🥴), thinking he’d be cool about it….sent me away with a flea in my ear and basically told me not to waste his time. Never made that mistake again!

Susie Wilson (1994)

I once went to a party themed on the letter P dressed as Roy, complete with cardboard glasses, beard and sandals, borrowing a certain Classics student’s trousers & jumper for the event. Roy passed me in main quad and gave me a look I am unable to describe, beyond that it was typically initially inscrutable, sardonic yet warm.

Mark Ashurst (1989)

None of us could forget those electrifying tutorials, whether Roy appreciated your essay or not. He was – in his intentional, deliberated way – always a firestarter. It often felt like too much to take in, too many synaptic sparks were igniting at the same time. Emerging from the fug of pipe smoke, I felt a kind of mental charring, as traces of more-than-earthly vapours fizzed through our brains.

Only in the following days – decades, it turned out – would the next round of new doubts, thoughts and interrogations spring up from our scorched brain tissue. Small details are etched into memory. There’s no such thing as a quote; we had to quote every quotation, writing the noun in full. Transcendental is not a substitute for the transcendent; this following another of Roy’s crucial distinctions, between imminence and immanence.

I had come to Univ to read PPE. My subsequent jobs still involve those subjects, in the workaday worlds of Mammon, media, politics. But in navigating them, I’ve had frequent cause to think about Roy. At Univ, midway through my first year, I had told him my naive, idealistic, inherently grandiose suspicion that what we did at college – this Education – would be formative, but perhaps (for me) not in a good way. We were acquiring a Worldview. I thought that a real Worldview is literary, though I couldn’t say why. Any other manifesto – Economic Structural Adjustment, Sustainable Development Goals – seemed wanting.

None of this was particularly convincing, as you can imagine. I struggled to explain: I didn’t have the Romantic view, so I didn’t know how. I actually liked PPE, but wasn’t deterred by its logical view. A sympathetic politics tutor tried, generously, to address this conceit: I would be disappointed by the English syllabus, she suggested, since it was fairly certain that even students of literature were expected to write logically too. Even now, it’s startling that so great a gulf separates the preoccupations of Romanticism – that Rumble of Reason and Emotion and the sovereignty of individual Imagination — from the other disciplines.

Helen and Roy were generous. They didn’t want another English undergrad on their books, but forgave this one. I’ll always be grateful that they allowed me to join.

After Univ, I went to Johannesburg to try my luck as a journalist. I found Southern Africa to be freighted with Romantic ideas, and not just from the Mission Schools or colonial intellectuals. Africa’s tumultuous democratisation was loaded with end-of-days rhetoric, unearthing the ghosts of Revolution in France. By then I’d written occasional cards to Roy, who always replied. His Romantic perspectives were like a set of keys. The meaning, of anything, seems always to require unlocking.

Privately I clung to such ideas when I joined the Financial Times in the mid-1990s. There wasn’t much room for romanticism in those pink pages, but the keys still came in handy. Essay topics we tackled at Univ felt suddenly useful and relevant to a reporter-at-large: Shakespeare mattered to the Struggle in Soweto. The hustle and gangsterism of Elizabethan England spoke to the same condition, an eschatology.

Dust. Poverty. Dignity. Sunshine. Limousines.

Here were autodidacts, guerillas, troubled and sometimes brilliant souls — a progeny of the incredible violence of colonial Africa. The best of them leaning (as we say now) into Romanticism. On my 24th birthday, I stood in an ululating crowd on the lawns of the Union Buildings in Pretoria watching the inauguration of President Nelson Mandela. After him, a new Deputy President took his oath of office behind the bulletproof glass: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” announced Thabo Mbeki. Of course he did, you might think, but then he digressed from Wordsworth: “But to be part of it was very heaven”. I felt the synaptic sparks lit up and flew again — it was like being in Roy’s study.

These days, my job is in industrial decarbonisation. Mostly I work on so-called « hard-to-abate » sectors: the emissions-intensive processes of a steel furnace, cement plant, jet fuel or ethylene cracker. Much is happening in heavy industry and transport to curb global heating to a Paris-aligned 1.5 degrees.

Three decades on, none of this feels far from the ideas that Roy banged on about, banged into us. We’re living in (another) age of extremes, but also of enlightenment. The apocalyptic dimensions of climate emergency need no elaboration. And the same time, we know already how to fix it: the clean technology is here, it’s bankable, costs of inaction are higher than those for a clean transition even in purely financial calculations. Two converging paths for green energy and materials lie ahead, well charted. First Movers are blazing a trail in science and in industry, at pace and scale.

The obstacle isn’t in politics or policy or capital markets — or anywhere else from the provenance of the structural world. Why can’t we sort ourselves out? The answer, like the problem, is stubbornly human — and a failure of perception. To really see our frailty, through the Anthropocene of our greenhouse gas emissions – we would need also to see its corollary: the powers of reason and the imagination – of a Romantic perspective. I wish Roy were here to help with that, but of course he is.