A White Dogge Called Boye

Page from a royalist propaganda pamphlet, depicting of the death of Boye at the Battle of Marston Moor. Printed in London, 1644, artist unknown.

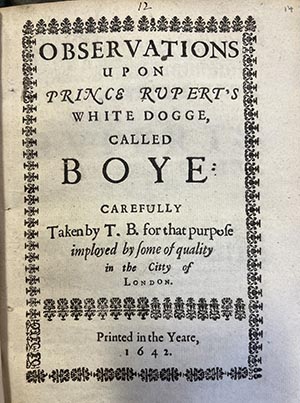

In this month’s Treasure, we take a look at a peculiar 17th century parody held amongst Univ’s collection of early printed books. Observations Upon Prince Rupert’s White Dogge Called Boye is a short, ten-page satire printed in 1642, the first year of the English Civil War.

Prince Rupert of the Rhine, nephew of King Charles I, was a successful commander of the Royalist cavalry during the English Civil War. As a teenager in Austria, he was gifted a white hunting poodle named Boye (or Boy) who travelled with Rupert back to England. The dog accompanied Rupert into several victorious battles, and Boye quickly became a mascot for the Royalist military campaign. As nephew of the King and a symbolic Royalist Cavalier, Rupert was the subject of much Parliamentarian propaganda; one target of this propaganda was Boye, who was claimed (and believed) to be a witch’s familiar that possessed magical powers and committed evil deeds at the behest of his master.

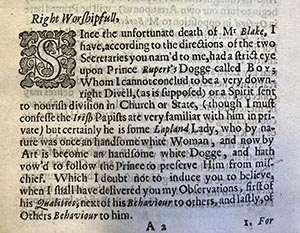

“I cannot conclude (Boye) to be a very down-right Divell, (as is supposed),” page 1 (Click for larger image)

Observations is a Royalist satire written pseudonymously by “T.B.”, a soothsaying-mystic character who claims to be spying on the dog and reporting back to his Parliamentarian employers details of the dog’s occult abilities. Throughout, the text mocks the Parliamentarians’ superstitious beliefs, as well as their losses incurred during the war. T.B. starts his satire with an emphatically absurd claim regarding the belief that Boye is the devil incarnate: “I cannot conclude [Boye] to be a very down-right Divell, (as is supposed) or a Spirit sent to nourish division in Church or State”. Rather, the author puts forth the equally ludicrous alternative that the dog is in fact “some Lapland Lady who by nature was once a handsome white Woman, and now by Art is become an handsome white Dogge, and hath vow’d to follow the Prince to preserve Him from mischief.”

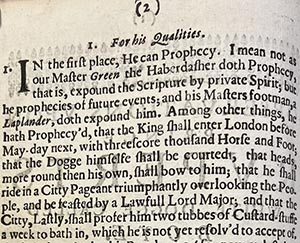

“The Citty, lastly, shall proffer him two tubbes of Custard-stuffe a week to bathe in,” page 2 (Click for larger image)

In another of the text’s more preposterous claims, T.B. observes that the dog can prophecy. Among his prophecies, Boy predicts that King Charles “shall enter London before May-Day next, with threescore thousand Horse and Foot”; that “the Dogge himself shall be courted”; that “he shall ride in a Citty Pageant triumphantly overlooking the People”; and finally, that “the Citty, lastly, shall proffer him two tubbes of Custard-stuffe a week to bathe in, which he is not yet resolv’d to accept of.” This absurdist humour is delightfully bonkers, and the author’s grandiloquent, run-on sentences render it ambiguous as to whether it is the dog or the Prince who shall receive tubs of custard to bathe in.

Observations was evidently written at an early stage of the civil war, when the Royalist faction had reason to feel boastful about their position. In a section titled “For his qualities”, T.B. describes some of the powers he has observed in Boye, and how the dog has used these powers to defeat the opposition. Included in Boye’s repertoire of witchcraft is the power of invisibility, which the dog has apparently employed to free captured Royalists:

“He can goe invisibly himself, and make others doe so too. He hath often been where no body hath seen him, and done that that no body else could. Who think you convinced Oneal out of the tower: even BOY. Who conceived the Lord Digby first into Hull, afterwards out again? Even BOY. Who got Legg out of prison? Even BOY. Who released Bamfield? Verily BOY still.” [sic]

Referring to the imprisonment and escapes of, respectively, Daniel O’Neill, George Digby, William Legge and Joseph Bampfield, the author mocks Parliament’s repeated losses and pokes fun by attributing these to the dog’s supernatural machinations. How could the opposition so often misplace its prisoners? Verily, a logical explanation must be that an invisible dog is flighting them away:

“I beseech you have an eye out for yourselves; for he goes oftener between Oxford and London, every week, then the three Carriers doe… upon my certain knowledge he doth usually breathe a black cloud around Prince Rupert too, in which he goes as invisible as our Church, or our Faith doth, or as our Charity should. And by this mystical meanes ‘twas, that the Prince so often passed our Guards undiscovered, & by so many disguises entred those Townes of Ours.”

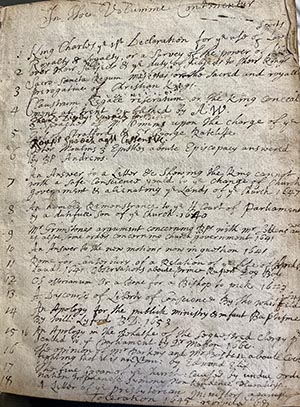

Manuscript contents page for the bound volume that contains Observations Upon Prince Rupert’s White Dogge Called Boye (Click for larger image)

This satire appears to be quite rare, and it is curious that it should come to be in Univ’s collection but not present in others. According to WorldCat, Univ’s is the only copy in Oxford University, and one of only four extant print copies in the UK. We cannot be sure how this text made its way into our collection but, in Univ’s edition, it is notable that it is bound in with 17 other pamphlets. Most of these other texts concern the superiority of the monarch or seek to reinforce the sanctity of their rule, such as Royalty and loyalty, or a survey of the power of kings over their subjects & the duty of subjects to their kings; and Sacro-sancta Regum majestai, or the sacred and royall prerogative of Christian Kings. So it is odd that bound-in with such pious works we find this slightly bizarre parody that, while mocking of the losses and beliefs of the Rebellion, never explicitly extols the qualities of Prince Rupert or indeed King Charles.

But, in a rather romantic coincidence, college does claim a direct interaction with the subject of this text. College accounts show that in 1642/3, £2 12s. 6d. was paid “to the trumpeters, footmen, and coachmen of the Prince of Wales and of the King, and to the trumpeters of Prince Rupert” (Robin Darwall-Smith, p.167). It feels appropriate then, that Univ should count this satire amongst its collections, so that we might continue to trumpet the qualities of Prince Rupert or, more accurately, those of his White Dogge Called Boye.

Title page of Observations Upon Prince Rupert’s White Dogge Called Boye, by T.B

Bibliography

II.6.5 T.B.: Observations Upon Prince Rupert’s White Dogge Called Boye : Carefully Taken by T.B. for that purpose imployed by some of quality in the Citty of London (London, 1642)

References

Robin Darwall-Smith, A History of University College Oxford (Oxford University Press, 2013)

Edward Hyde, Earl of Clarendon, The history of the rebellion: a new selection (Oxford University Press, 2009)

Ian Roy “Rupert, prince and count palatine of the Rhine and duke of Cumberland (1619–1682), royalist army and naval officer.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2011)

Further selected Univ Treasures are detailed below or explore the whole collection on our News and Features Treasures pages.

Published: 26 July 2023