What’s in a name?

Cross-gender names and naming traditions in Roman Egypt

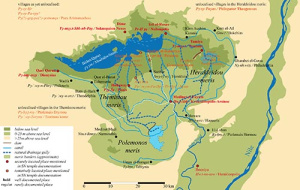

Map of the Fayum (drawing by S. L. Lippert / M. Schentuleit)

Ancient Egypt, renowned for its monuments, also reveals fascinating insights through its texts written on stone, papyri and sherds, which offer a glimpse into the society’s intricate naming traditions, including the existence of cross-gender personal names.

In the Graeco-Roman period, these names were a notable phenomenon in some settlements, especially Dime (Soknopaiou Nesos), located in the Fayum region. The use of cross-gender names – names employed interchangeably by both male and female individuals – is particularly surprising given that Ancient Egypt was a highly gender-differentiated society. This provokes research into the reasons behind this practice, exploring the linguistic, religious, and social influences that rendered these names so popular in Dime.

Egyptian personal names

In Egyptian culture, personal names generally have a meaning. Alongside personal names that make direct reference to the name-bearer and their family (e.g. Iuefaa “He will attain old age”), numerous names refer to a god (e.g. Merisekhmet “Loved by (the goddess) Sekhmet”), the ruling (or an earlier) king (e.g. Ramessunekhet “Ramses is victorious”), or some venerated individual (e.g. Tasheretiuefankh “The daughter of Iuefankh”). In some cases, the meaning is not obvious to us; names can, for example, be abbreviated comparable to Mel, Melly or Lanie as short forms of Melanie, a female name with Greek origins meaning “black” or “dark”. An Egyptian example would be the popular name Peteosiris, meaning “He who was given by (the god) Osiris”, which appears barely recognisable when shortened to Pasis. Many names are genderspecific because they have an element that indicates the gender of the name-bearer, like the already mentioned “The daughter of Iuefankh”. There is also the group of gender-neutral names, such as the above-mentioned “Ramses is victorious”, names that at first glance reveal nothing about the gender of the name-bearer.

The ruins of the Temple of Soknopaios at Dime (Photo: M Schentuleit)

Dime: A unique case study

A case study on the onomastic material of Dime determines factors that classify a name as cross-gender. This settlement, dominated by a large temple dedicated to the god Soknopaios and located on the northern shore of Fayum Lake, is particularly well-suited for such a study since cross-gender names were relatively common in the Roman period (30 BCE–3rd century CE), as evidenced by the extensive textual records in demotic, the second-to-last indigenous language and script phase, and in Greek, the language of the administration left behind by the sizeable priestly community.

Linguistic features

The group of cross-gender names in Dime consists of four names: Stotoetis “May they (i.e. the gods) avert the calamity”, Tesenouphis “(The) good nomos” or “The good sea-land (i.e. Fayum)”, Herieus “They (ie the gods) are satisfied” and the Aramaic-rooted name Satabous, of which the meaning is not entirely secure; originally possibly “Sister of the father” but this is far from sure. It is striking that the three Egyptian names lack gender-specific markers, underscoring linguistic neutrality as an important characteristic for using these names across genders. However, not all gender-neutral names were indeed used for males and females.

Religious roots of cross-gender names

A key factor driving the use of cross-gender names in Dime was their association with deified individuals who were worshipped as local gods. For the deified Tesenouphis, a statue was dedicated in Dime (I. Fayoum I 79, 30 BCE – 50 CE), and he is recognised as an oracle god of a Fayum town called Pernakheru (P. Hawara 4 a and 4 b, 220 BCE). Stotoetis the god, the great god is mentioned in unpublished demotic agreements relating to Gynaikon Nesos, one of the branch sanctuaries of Dime in the western part of the Fayum and as an oracle god in an unpublished oracle question from Tebtunis (2nd cent. BCE). Satabous the god had a cult in the chapel of Isis Nepherses in Dionysias, another branch sanctuary of the main temple in Dime. Attestations for a deified Herieus are still to be found; a previously assigned votive inscription likely refers instead to the dedicatee of the statue (I. Fayoum I 80, 50 BCE–50 CE).

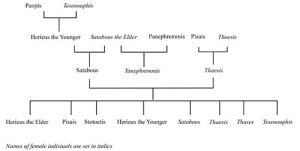

Family tree of a priestly family from Dime (drawing by M. Schentuleit)

Social and familial traditions

Scholars noticed early on that Dime’s onomastic repertoire was quite limited. This impression can now be confirmed statistically. Almost a third of all male name attestations are represented by six different names – among them all four cross-gender names – and seven different names represent a third of all female name attestations – among them two cross-gender names. This is due to the naming traditions in Dime and other priestly communities deeply rooted in family lineage and religious practices: Firstborn children were often named after their grandparents, the firstborn son after the paternal grandfather, the secondborn after the maternal grandfather, the firstborn daughter after the paternal grandmother, the secondborn after the maternal granddaughter, and subsequent offspring were named after other relatives. An illustrative example is the family of a certain Satabous and his offspring who were eminent figures among the priesthood of Dime. Satabous himself even shared the same name with his mother. The naming practice, together with the community’s isolation and a strong emphasis on intermarriage among priestly families, created a limited pool of names within the priestly families, leading to frequent repetition. Thus, the large proportion of cross-gender names in the onomastic material from Dime results not only from the significance of deified individuals for the priestly milieu but even more so from social traditions.

A broader historical perspective

The phenomenon of cross-gender names in Roman Dime mirrors practices in some Roman Catholic regions, where names of eminent biblical figures like Maria or Joseph are used by both men and women (eg Carl Maria von Weber [1786–1826], German composer; Josemaría Escrivá [1902–1975], Spanish priest and founder of Opus Dei). In Dime, it reflects the interplay of language, religion, and social structure. While the practice was more pronounced in certain regions and periods, it offers a unique window into the complexities of Egyptian culture. The study will be published as “Egyptian cross-gender names in Graeco-Roman Dime and beyond”, in: A Almásy-Martin and Y Broux (eds.), Greek Personal Names in Egypt (Oxford Studies in Ancient Documents, Oxford University Press, 2025).

Dr Maren Schentuleit, Lady Wallis Budge Fellow at Univ, Associate Professor of Egyptology and Coptic Studies in the Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies and Director of the Griffith Institute

This feature was adapted from one first published in Issue 17 of The Martlet; read the full magazine here or explore our back catalogue of Martlets below: