She before Sherlock

The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective: a new book by Univ alumna Sara Lodge, reveals the surprising truth about real Victorian women sleuths.

Dr Sara Lodge

Most dons are detectives at heart. We unearth clues to the authors of shocking deeds. We rescue bodies of work from the cruel river of time. Sometimes, we take on cold cases that take years to thaw.

My tale begins, as many detective stories do, in a library. In 2012, the British Library reissued two books from 1864 that had puzzled literary historians. Both pulp fictions – The Female Detective, by James Redding Ware, and Revelations of a Lady Detective, by William Stephens Hayward – posed as casebooks by female private investigators who solved complex mysteries using forensic evidence, archives, undercover identities and subtle interview technique. The curious thing, as the introduction to one of these reprints proclaimed, was, there were no real female detectives in 1864. Moreover, the female detective as a literary character seemed to go underground after this, reappearing only in the 1890s.

Something, as they say at crime scenes, just didn’t make sense. Why would two books appear in one year featuring a character with a job description that didn’t yet exist? Provoked, I scoured newspaper databases, looking at the small ads. Almost at once, I found back-to-back ads in The Times for two London private enquiry agencies in the 1870s offering “experienced” male and female detectives. I was on the scent.

Something, as they say at crime scenes, just didn’t make sense. Why would two books appear in one year featuring a character with a job description that didn’t yet exist? Provoked, I scoured newspaper databases, looking at the small ads. Almost at once, I found back-to-back ads in The Times for two London private enquiry agencies in the 1870s offering “experienced” male and female detectives. I was on the scent.

Over the next ten years, I built up an astonishing picture (well, astonishing to me) of Victorian women’s routine involvement in crime-solving. I traced Elizabeth Joyes, born to a thatcher in rural Cambridgeshire, who became a “detective searcher” at St Bride’s police station near Fleet Street, examining female suspects for stolen goods. She was “employed as a female detective” outside the station, too; in 1855 she captured John Cotton Curtis, a serial luggage thief at railway stations. Then there was Ann Lovsey, a “searcher” at Birmingham’s Moor Street station for at least 36 years, from the 1860s to the 1900s. Lovsey became “well known as a female detective” in Birmingham, apprehending malefactors from spurious psychics to embezzling bus conductors. Women detectives were rarely involved in murder cases, but they did engage in risky sting operations to capture thieves, back-street abortionists and child abusers. From Glasgow to Dover, working-class women – often related to male police officers – were putting their bodies on the front line.

Women were also working for private enquiry agencies, investigating everything from aggravated adultery to large-scale corporate fraud. Some ladies, such as actress-detective Kate Easton and multi-lingual entrepreneur Antonia Moser, ran their own agencies. As the chorus line in one 1890s musical about an all female agency sang: “A bevy of lady detectives are we; Clever and cute as detectives can be.”

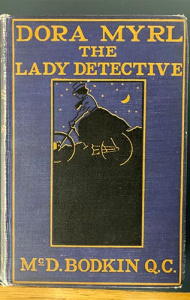

By the 1890s, magazines reported that even female graduates of Oxford and Cambridge University were becoming detectives. Hearth and Home conceded that “This is not an occupation that many ladies would like, but apparently there are some who think differently. We have heard of one, a University graduate, who engages in it simply because it has an irresistible fascination for her.” Fast, fictional “New Woman” detectives on their bicycles, including Lois Cayley and Dora Myrl, were on the trail not only of male malfeasance, but of equal rights.

By the 1890s, magazines reported that even female graduates of Oxford and Cambridge University were becoming detectives. Hearth and Home conceded that “This is not an occupation that many ladies would like, but apparently there are some who think differently. We have heard of one, a University graduate, who engages in it simply because it has an irresistible fascination for her.” Fast, fictional “New Woman” detectives on their bicycles, including Lois Cayley and Dora Myrl, were on the trail not only of male malfeasance, but of equal rights.

Florence Marryat, a sensation novelist, invented a heroine who becomes a counterterrorist agent in her 1897 novel In the Name of Liberty. Jane Farrell will discover that the Fenian terrorist who is about to blow up the Earl of Innisfale’s London mansion is actually…her husband. This is a literally explosive development in the Victorian marriage plot. Marryat, who despised male political domination, also invented a future female don in 1893, Electra Thucydides of St Momus College, Oxford – who, in an imagined lecture of 1993, broadcast “telephonically” to over 200 female audiences, asked “What shall we do with our men?”

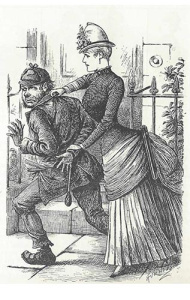

Where previous commentators had wondered why the fictional female detective “disappeared” between 1864 and 1890, my research uncovered her popular presence on the Victorian stage from the 1860s to the 1890s: a fist-swinging, ball-busting, often cross-dressing character who always got the better of villainous males.

After cyber-crime crippled the British Library in 2023, I was grateful to be able to complete my book in the Bodleian. The aroma of old tomes and the sight of a student scribbling at his desk in full Edwardian dress hit me with a wave of nostalgia. It was satisfying to close the circle, looping back to my time as a doctoral student at Univ. Back then, I had no idea that I’d be investigating undercover Victorian sleuths, the shadows of a forgotten female history.

Professor Sara Lodge (1994, English), writer and Senior Lecturer in English at the University of St Andrews

Professor Sara Lodge, The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective (Yale University Press, 2024)

Professor Sara Lodge, The Mysterious Case of the Victorian Female Detective (Yale University Press, 2024)

This feature was adapted from one first published in Issue 17 of The Martlet; read the full magazine here or explore our back catalogue of Martlets below: